Lakerda and Istanbul's plethora of fish

Ask any Istanbulite what the defining component of the city’s culinary and drinking culture is and more often than not the answer will be mezze. Made from a rich variety of ingredients – greens, legumes, aubergines, yoghurt, fava beans, courgettes, cucumbers, pomegranates, mussels, liver, walnuts, feta cheese, and countless others – the mezze is a world unto itself. And lakerda – preserved Atlantic bonito or sarda sarda – is the undisputed queen of this world.

Food for Gods

What is it that makes lakerda to stand out amongst its succulent rivals? Well, lakerda has such an enchanting taste that one could easily take it for the food of Gods, of Olympian deities that indulged only in nectar and ambrosia. And this is how author Tan Morgul pictures it in a short story about a fictitious encounter between Zeus’s wife Hera and poet Archestratus.

The story is set during the 4th century B.C. journey Archestratus made from Syracuse (in Sicily) to Sinope (on the Black Sea coast). The poet spends more than a fortnight in Byzantium (later Constantinople and today Istanbul) where every evening he enjoys the richest seafood dishes known to humankind. During one of those evenings Poseidon, disguised as a seal, emerges from the sea and tells him that Zeus’s wife Hera had found out about his affair with Io and that the God of Gods bids him to occupy his wife for a while so that she won’t be able to lay her hands on his lover.

All Archestratus has to do is to prepare Hera’s favourite dish – what else but bonito – and the aroma will simply draw her to his table. The poet does as told and goes way beyond his order, garnishing the table with dried mackerel, taramasalata made with swordfish eggs, black mussels, oysters, and of course Lesbos wine.

Lo and behold, Hera appears, disguised as an elderly Byzantine woman, and despite being in a rush, is so intrigued by the dishes set before her that she decides to stay and spend the evening at Archestratus’s table.

She is delighted with the food and the wine, of which she consumes copious amounts, and decides to return the favour by giving the poet, in her own words “an Olympian recipe straight from the table of the Gods”. The dish – preserved amia (the ancient Greek name for large bonito) – is called lakerda on Mount Olympus and is a true favourite of all the Gods; a divine delicacy befitting the Queen of Cities (as Constantinople came to be known).

In his article on the origins of lakerda, Tan Morgül says he came across the “first” reference to lacertos (the Latin origin of lakerda) in Publius Papinius Statius’s Silvae, a collection of 32 poems written in Latin during the 1st century. In it, Statius complains that a variety of pungent smells, including that of cooked Byzantine lacertos had permeated a book he borrowed from someone named Grypus. As Statius was not a gastronome, we cannot be sure of which fish and what cooking method was used to make lacertos but the text is important as it is the earliest Istanbul-related piece, which includes a reference to lakerda.

How to make delicious Lakerda?

Although European travelogues visiting Istanbul over centuries have misidentified the main ingredient of lakerda as Spanish mackerel, horse mackerel, chub mackerel, and tunny (either because they lacked the scientific knowledge to distinguish between different types of fish or because they wanted to use fish their readers were familiar with for them to be able to imagine the taste of lakerda), its recipe has not changed significantly for centuries. Leading culinary expert Vedat Milor believes the most delicious lakerda available in Istanbul is prepared by a fisherman by the name of Resul Reis from Şile (a borough in northern Istanbul on the coast of the Black Sea). So, this is how to make lakerda that impresses even the most discerning palates.

“I only use fish that I’ve caught because to make lakerda I need to know how it was caught and treated. Fatty Atlantic bonito weighing around five kilos is ideal for lakerda. Once I cut it into wedges, I drain all the blood and remove the marrow. Draining of all the blood is key. Keep the wedges in salty water in a fridge for 15 days. Salt the pieces, wrap them in oiled paper, and store for 15 days. Once the pieces are entirely drained, I clean them and put them in real olive oil. The jar they are in must be air-tight. That way, you can keep them for as long as you want. A month, a year, two years.”

Vedat Milor: “The harmony between rakı and the salty, iodine taste is simply remarkable. One bite of lakerda, one sip of rakı…”

Aylak Lakerda

A plethora of fish

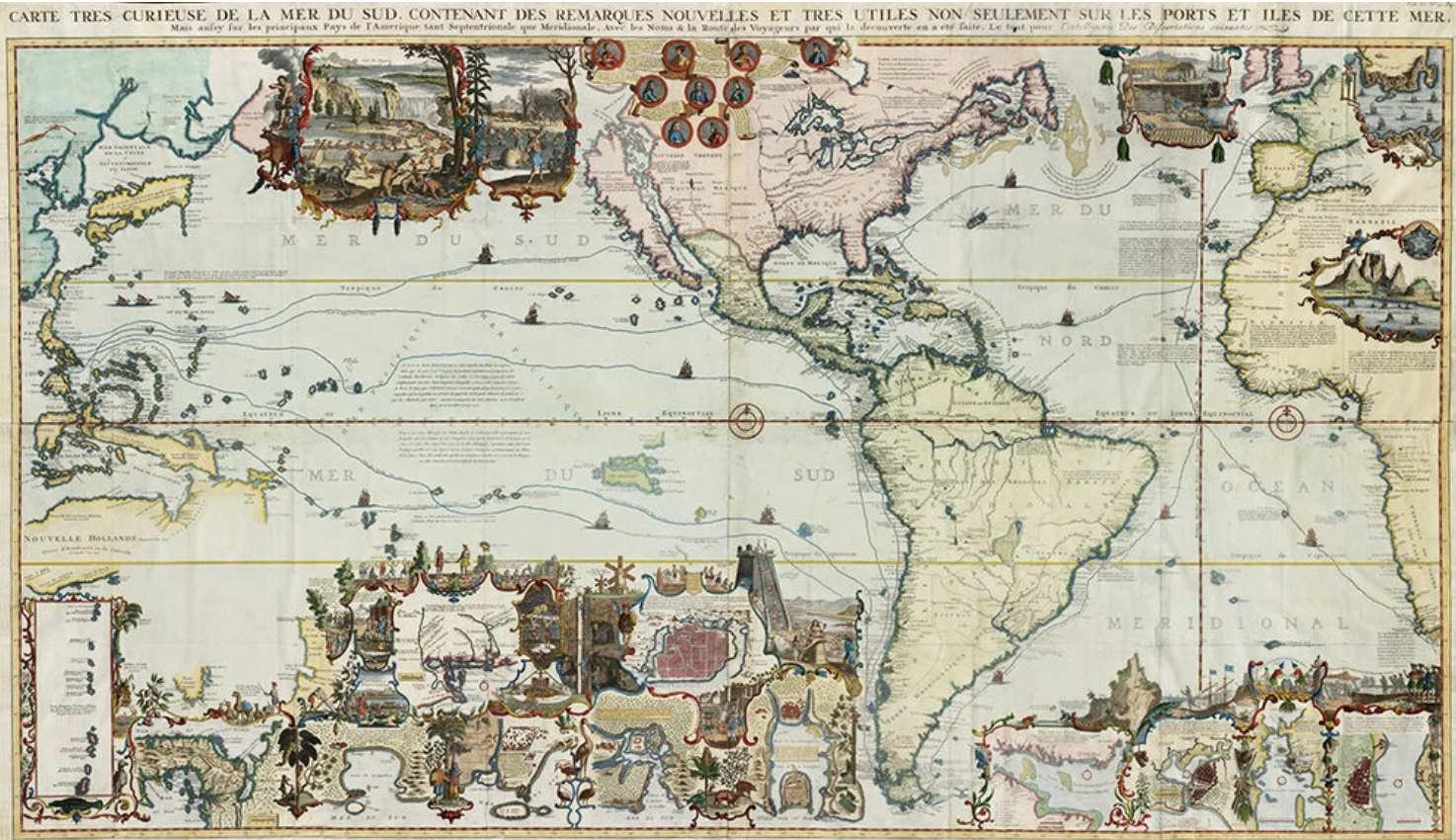

There is a material, worldly reason as to why lakerda has remained at the heart of the city’s mezze culture for centuries and that is Istanbul’s unique location and character. Istanbul’s spatial and geographical idiosyncrasy – as the only city on earth that sits on two different continents, at the convergence of Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East – has made it the quintessential imperial capital, a vibrant hub on trade routes from time immemorial, and in traveller Gérard de Nerval’s words, “a magical seal that unites Europe and Asia since ancient times.” That uniqueness has had a lesser-known and yet pivotal impact on Istanbul’s culinary culture: a cornucopia of fish swimming in and through its waters.

Being squeezed in between two seas with very distinct features (the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara) and sitting on a strait has meant Istanbul is the passageway for a plethora of fish migrating to and from warmer waters. Of such prominence was this plenitude that almost every traveller writing about Istanbul dedicated pages to it, describing in detail the central place seafood occupied in the city’s cuisine.

Indeed, no one could ignore this “blessing” that halted the advance of Alexander’s ships in the Sea of Marmara one day and changed the colours of the sea on another. The first person to mention the abundance of fish in the Bosporus was Homer in the 8th century B.C. And, almost a millennium later, Roman naturalist author Plinius couldn’t hide his amazement at the “branchial darkness” that descended on the Golden Horn:

“Near Kalkhedon (now, Kadıköy), there is a magnificent, glittering, white rock that springs up from the bottom of the sea. When a school of bonitos comes across it, they are so frightened by its dazzling sparkle that, they turn around and swim towards the Byzantian Peninsula. And, that is why it is called the Golden Horn…”

In Taste of Istanbul’s chapter dedicated to fish, Sula Bozis quotes Pierre Gyllus who visited Istanbul in the mid-16th century. The visitor’s observations are a testimony to the abundance of fish in the capital:

“…Venice, Marseilles, and Taranto are famous for their rich variety of fish but Istanbul is in a league of its own. The Bosporus is teeming with fish coming from two separate seas. At any point in time, there are such mass quantities of it swimming on these shores that residents can catch them with their bare hands. In the spring, people hunt schools of them swimming towards the Black Sea by hurling stones at them. And women living in houses on the shore simply dip baskets into the water, which are filled to the brim with fish when taken out.”

The famous Ottoman explorer and traveller Evliya Çelebi mentions 2,246 different types of food in his 17th century Seyahatname (Book of Travels). Of those, 140 are different varieties of seafood: 93 species of saltwater and fresh water fish; 16 kinds of crustacean and mollusc shellfish; 31 different types of fish by-products such as caviar or processed fish. According to Çelebi, 700 people were employed in 300 fisheries around Istanbul and the industry was strictly regulated. For instance, there were strict rules regarding meeting the fresh fish demand of the urban population first and then using salting, drying, or smoking techniques to preserve the excess supply.

Preserving the Atlantic bonito

The sarda sarda family is amongst the fish that migrate through the Bosporus. Most lay eggs in the Black Sea in the spring and bonitos start their migration to the Aegean Sea via Marmara in mid-September. Their bigger and fatter family member, the Atlantic bonito follows track in mid-October. And that is when lakerda lovers’ eager wait for the new patch of the queen of mezzes begins.

During the golden days – or rather, centuries and even millennia – of the Bosporus ecosystem, this abundance of fish in general and sarda sarda in particular, and having a manageable urban population meant significant amounts of Atlantic bonito bore the risk of rotting away. (Numbers from 1911 draw a clear picture of the seriousness of the situation. According to official records, approximately six and a half million Atlantic bonitos landed in the Istanbul fish depot. The population of the city at the time: one million.) So, to prevent what would in culinary terms be a traumatic experience, the early residents of the city came up with a way to preserve the bonito so that they could treat themselves to delicious lakerda whenever they pleased.

Exponential population growth, unbridled industrialization, incompetent governance, and the resulting environmental degradation mean the Bosporus and its surrounding waters are no longer teeming with Atlantic bonito. Today, lakerda is often made with its smaller relative, the regular bonito, meaning real lakerda has become an even more precious delicacy. And you can no longer come across Armenian vendors selling lakerda they have made with the Atlantic bonito they have caught from their glass carts.

The Atlantic bonito (sarda sarda) is a large fish that belongs to the family Scombridae. It is common is shallow waters of the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea. It can grow up to 75 centimetres and weigh up to 6 kilograms at that size. Smaller bonito are usually grilled as steaks whereas large Atlantic bonito are preserved as lakerda.

However, offered mostly in meyhanes where Istanbulites take delight in communal feasting and the company of others, lakerda continues to be an indispensable part of Istanbul’s culinary culture. After all, lakerda is not merely preserved fish, but a dazzling symbol of this eternal city.