Istanbul as Spectacle

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, source: Bostabure

Once it was decided that London would host the first international exhibition in history, the next question that faced British authorities was where an organization of such magnitude would and could take place. As there were no buildings spacious enough to host such an event, a new structure would have to be erected for the occasion. All parties involved, including Prince Albert, who was an ardent supporter of the exhibition since the earliest days, agreed upon the southern side of Hyde Park (near Knightsbridge Road) as the ideal location for the new building. The public, however, had doubts about erecting a structure in Hyde Park that was not temporary. So, during the debates in the House of Commons, the designer Joseph Paxton submitted a plan for a structure made chiefly of glass and iron, similar to the glasshouses he had successfully built in Chatsworth. And, that is how the spectacular Crystal Palace, which the Ottoman author Namık Kemal likened to a diamond mountain formed by continuous refraction of lights, came into being.

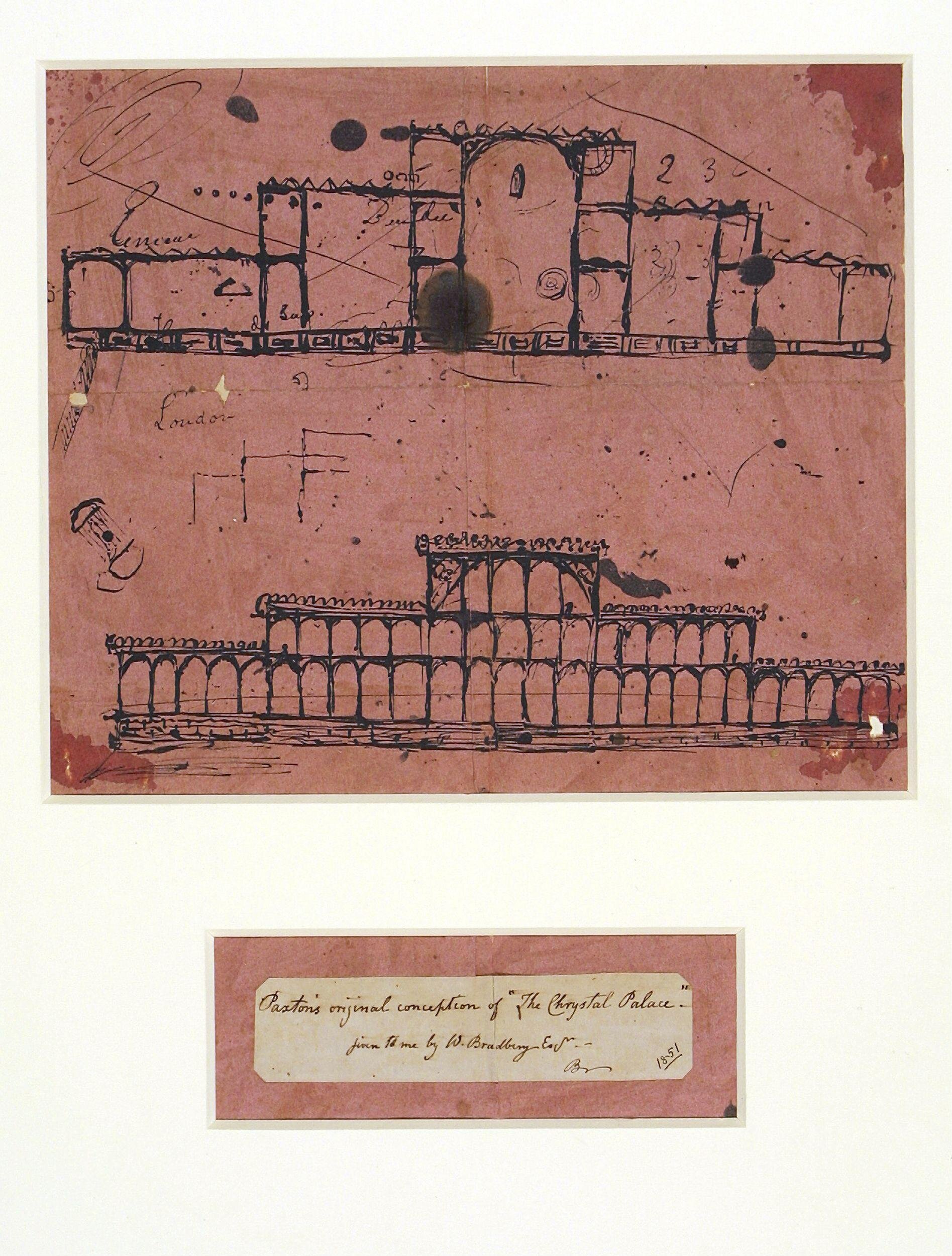

Joseph Paxton's first sketch for the Great Exhibition Building, c. 1850, using pen and ink on blotting paper, source: wikipedia

View from the Knightsbridge Road of The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park for the Grand International Exhibition of 1851. Dedicated to the Royal Commissioners., London: Read & Co. Engravers & Printers, 1851, source: wikipedia

The Crystal Palace was designed as a parallelogram 560 meters in length, 125 meters in width, and 39 meters in interior height. More than 300,000 meters of glass was used in the construction of the building, whose large size (three times that of St. Paul’s Cathedral) was emphasized by the trees and sculptures Paxton placed inside during the Exhibition. As Yvonne Ffrench noted, the Crystal Palace was an architectural marvel and an engineering triumph that demonstrated the importance of the Exhibition itself. The structure was moved and re-erected at Sydenham Hill in south London in 1854 and destroyed by fire on November 30, 1936.

Left: The Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1854), Right: The Crystal Palace completely destroyed, a few days after the night of 30 November 1936, source: wikipedia

The world Daguerreotyped

When American William Andrew Drew visited the Exhibition, the first thing that drew his attention was the lack of green grass on the path that led to the Crystal Palace – an indication of the hitherto unimaginable number of visitors the fair had attracted. Once inside, he stood still and gazed at the world before him: aisles were lined up with participating nations’ pavilions, each furnished with a floor room, elevated platforms, pyramidal shelves, counters, tables, and glass cases resting against walls for the display of curious artifacts. “The world Daguerreotyped stands before me,” he mused.

“Such a bazaar as only an Eastern genii might have created.”

The Foreign Department, viewed towards the transept. The interior of the Crystal Palace in London during the Great Exhibition of 1851, source: wikipedia

The scenes inside Crystal Park, which hosted 34 countries plus Great Britain and its colonies, effectuated a similar state of fascination in all visitors. The most precious products lining up the long passages, rich tapestries hanging from lofty galleries, the kaleidoscopic canopies, the hum of voices, strange faces, mixed costumes, and the perfumes of scented water “all contributed to form a world such as only had been imagined in Eastern fables,” observed the historian of the Royal Arts Society the Illustrated Catalogue of International Exhibition of 1862. Charlotte Brontë concurred: “Its grandeur does not consist in one thing but in the unique assemblage of all things…Such a bazaar as only an Eastern genii might have created.” And, the Ottoman pavilion formed one of the most enthralling sections of this assemblage.

Illustrated Catalogue of International Exhibition of 1862, source: archive.org

An arrangement of infinite taste

According to Ottoman daily Ceride-i Havadis, Queen Victoria sent a personal invitation to Abdülmecid I, conveying her heartfelt wishes to see an Ottoman pavilion in the Exhibition. A bastion of modernization-cum-Europeanization, the Sultan leaped at the opportunity to share a platform with the world’s leading countries and so, the Ottoman delegate led by the future Ambassador Musurus Pasha and more than 3,000 artifacts in 200 cases set sail for Southampton on April 13th and arrived in London on April 26th. Cognizant of the abysmal state of Ottoman industry, the authorities wanted to showcase the quality of artisanship that characterized their products so most of the artifacts sent to London were items used in daily life – which was in line with the latest trends observed in museology at the time.

The pavilion had the air of an authentic Constantinople bazaar

The Ottoman pavilion was located in the “Torrid Zone”, halfway between the “civilized” world and “barbaric” countries. The pavilion was designed by the German architect (in exile in London at the time) Gottfried Semper. The heavily draped entrance, large swathes of fabric and carpets hanging from striped canopies, and the towering onion-shaped dome in the background created an air of an authentic Constantinople (read as exotic) bazaar. The “collection was arranged with infinite taste,” commended the authors of Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, and that pleased the visitors, “the majority of whom had read the Arabian Nights and longed to see with their own eyes the numerous illustrations of domestic manners of which their conception had previously been but imaginative, however accurate the description.”

Dickinsons' comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, Dickinson, Brothers, Her Majesty's Publishers, 1852, source: Smithsonian Libraries

There were quite a few Ottoman products and artifacts that captivated the visitors and organizers alike. Authors of the Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition 1851 were particularly impressed with the wine selection: “The Sublime Porte has contributed some white wines that are very well made, of good body and a brisk and very agreeable flavor. The best of these kinds have been produced from a Rhenish grape on Mount Olympus.”

Dickinson's Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Dickinson’s, on the other hand, drew attention to the hookahs, invoking images of the typical Ottoman we came across in travelogues: “The care taken in the manufacture of hookahs, beautifully ornamented with silver, shows how indispensable the pipe is to the Turk; indeed, he would hardly be recognized as such where he not luxuriously reclining on soft cushions, and dreamily listening to the ‘hubble, hubble’ noise made by the passage of the fragrant smoke of the tobacco through scented waters.”

Ornamented Hookah 1851, source: Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition, 1851 – Part V: Foreign States.

For the Art Journal, one of the highlights of the Exhibition was a cup made for the Ottoman Sultan by Monsieur Morel, who had spent some time in Constantinople before moving to Paris: “The enameled cup, executed for the Sultan, is richly decorated in the elaborate ornamental taste of the east and on its quatrefoils contains views of the principal buildings in Constantinople.”

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue – The Industry of All Nations, 1851

The International Exhibition of 1862 failed to create the same impact its predecessor did. Different reasons were put forward for this relative lack of success: Prince Albert’s death had dampened the mood in the capital; the weather throughout the fair was unwelcoming, to say the least; not enough time had passed since the last Exhibition to arouse the public’s curiosity. In any case, Ottoman contributions weren’t as flashy as well; the Empire’s economy had deteriorated in the last decade, and authorities debated whether spending invaluable yet scarce resources on an Exhibition made any sense. However, like an ailing man trying to prove to his younger relatives that there is still life in him, Ottomans decided to partake in the fair as they feared failing to do so would expose the Empire’s frail state to European powers.

Constantinople in Olympia

Constantinople in London, at Olympia by Joseph Holland Tringham.

So desirous was the British public for anything Ottoman during the second half of the 19th century that the Olympia in London hosted a special exhibit titled “Constantinople in Olympia” from Boxing Day in 1893 to mid-October 1894. This was, however, an exhibit quite unlike its predecessors – here, in Olympia, as Constantinople became a spectacle par excellence, the lines between the real and the imaginary were blurred, creating a surreal experience of the Orient for Londoners.

Olympia created a surreal experience of the Orient for Londoners

The exhibit included various landmarks of Constantinople including the Galata Tower, which offered a breathtaking view of the Golden Horn; the Grand Bazaar, where the visitors could find all sorts of Eastern curiosities; a “realistic replica” of one of the most beautiful mosques in Constantinople covered in marbles inside; the Rue de Pera, which offered a variety of magnificent attractions; cigarette manufacturing and carpet weaving ateliers where visitors could join “native workmen”; and most importantly, a caique trip from the Golden Horn to the Hall of One Thousand and One Columns “with its endless vistas of handsome pillars and arches”…Oh, and of course, an “authentic harem,” which must have been constructed using Lady Montagu’s descriptions she offered in her letters

As the visitors walked “beneath the Byzantine arches” lining up Constantinople’s streets, Roumelian bands entertained music lovers, and a “luxurious” Turkish restaurant offered delicious à la carte dinners. Last but not least, the visitors could enjoy “Constantinople; or, Revels of the East” – a revue directed by Hungarian Bolossy Kiralfy. In it, the young Duke of Orleigh undertakes a grand tour of Europe, traveling from London to Constantinople, where he rescues a princess from a gang of bandits. A pasha offers him invaluable gifts as a reward, but the Duke humbly declines them. The only thing he wishes to see before he leaves Constantinople is an “Eastern revel,” he explains. And, so begins the “Grand Ballet of the East,” with 2,000 performers singing and dancing in front of an Arabic palace, as foreign to Constantinople as possible. Well, this was, after all, the heyday of Orientalism.

Further readings

Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851. London: Dickinson, Brothers, Her Majesty’s Publishers. 1854.

Jeffrey Auerbach. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display. London: Yale University Press. 1999.

Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition, 1851 – Part V: Foreign States. London: Spicer Brothers and W. Clowes & Sons. 1851.

Robert Hunt. Synopsis of the Contents of the Great Exhibition of 1851. London: Spicer Brothers and W. Clowes & Sons. 1851.

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue – The Industry of All Nations, 1851. London: George Virtue. 1851.

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition, 1862. London: James Virtue. 1862.

The Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition, 1851. London. 1851.

The Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition, 1862. London. 1862.

William A. Drew. Glimpses and Gatherings during a Voyage and Visit to London and the Great Exhibition in the Summer of 1851. Augusta: Roman & Manley. 1852.