Phouskaria, Taberna, and Meyhane

Eski meyhaneler, source: istanbulapartmanlari.com

As Andrew Dalby notes in his seminal Tastes of Byzantium: The Cuisine of a Legendary Empire, to the Anglo-Saxon tradition as early as the 7th century, Byzantium was an empire of Winburga – that is, “cities of wine.” Wine, produced by fermenting grapes, was the outstanding alcoholic beverage available to Byzantine drinkers, and the residents of the capital enjoyed a wide range of the nectar of Dionysius, transported from the Thrace and western Asia Minor, the Aegean and the Black Sea shores, and sometimes even further afield. The locals called the establishments serving wine (and a few other less-favored beverages) and food (dishes made with fish, legumes, and meat) phouskaria while the Latin population referred to them as tabernae. Whatever their name, so magnetic were these salons that, according to contemporary chronicles, crusaders of the 13th century spent every waking hour imbibing wine in them.

Wine – An Indefatigable Clandestine Traveler

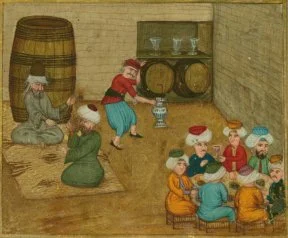

Tuhfet_ul Mulk

Any fears that Mehmed II, Sultan of the mighty Islamic Ottoman Empire, would have done away with the famed Byzantium taverns after conquering the city in 1453 proved unfounded. As French historian Fernand Braudel aptly put it, “The vine maintained itself throughout the land controlled by Islam and wine proved an indefatigable clandestine traveler.” Taverns near the port and around the arsenal continued to serve sailors and residents alike, and although Islamic law banned it, there is no doubt that among the clientele of the famed meyhanes (mey means wine and hane means house) of Constantinople were Muslim Istanbulites as well – a point made by many a European traveler such as Hans Dernschwam (a German traveler who visited Constantinople in the mid-16th century), Paul Rycault (head of the British envoy in Constantinople in the mid-17th century), and John Covel (priest at the British Embassy in Constantinople between the years 1670 and 1677).

Early Voyages in Levant by John Covel, source: bookfusion.com

Doubtlessly, the meyhanes’ modus operandi was strictly regulated: they had to be located in a non-Muslim neighborhood; they were not allowed to serve Muslims (a rule they broke quite regularly); the wine had to be transported from the docks to the taverns in casks; they had to observe strict opening and closing hours. However, none of these rules and regulations could decelerate the rising wine consumption or number of meyhanes in the city. In fact, such was the rise in the number of taverns and Istanbulites of all religions enjoying wine during the reigns of Beyazıd II (1481-1512) and Selim II (1512-1520) that Suleiman the Magnificent imposed the first carpet ban on alcohol consumption. It was the first but not the last prohibition on alcohol consumption in the empire, as until the 19th-century Westernization reforms, meyhanes existed in a vicious cycle – being banned only to be re-legalized in a few years and then outlawed again.

Osmanli Meyhane, source: Hubanname Zennenname

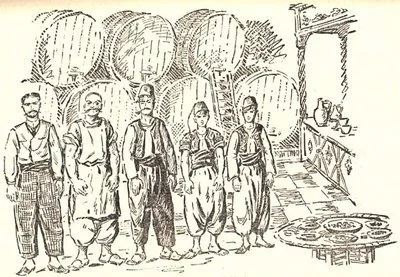

Hamse-i Atai, source: Hamse-i Atai

So, what caused this vicious cycle? The decision to ban meyhanes was often a result of pressure from religious circles or rulers’ security concerns and fear of social uprisings. However, revenues from alcohol tax amounted to a considerable part of the imperial budget, and officials knew very well that banning meyhanes would merely result in drinking in shady, illegal establishments. Of course, the Ottoman Empire was not the only polity that saw alcohol consumption and taverns as key financial resources. Indeed, one of the best-known examples of taverns funding the state is the Saladdin tithe, a.k.a. Aid of 1188, which was a tax levied in England in 1188, in response to the capture of Jerusalem by Saladdin in 1187. 100,000 silver marks were raised with the Saladdin tithe and a considerable amount of that came from the taverns and inns in England. Therefore, the bans mentioned above almost always ended up being relaxed or altogether discarded after a short period. During the early years of the 19th century, this vicious cycle finally came to an end, and as meyhanes gained unprecedented freedoms, Muslims started to feel more comfortable frequenting them.

As Close as It Gets to the Tavern of England

1830 The Eagle Tavern, in Hoxton/Islington, source: wikicommons

Taverns in London, as in the rest of England and Europe, served alcohol – mainly but not exclusively, wine – alongside an array of dishes – especially roast meats and cheese. At the entrance, there would generally be a sign with some sort of symbol, often related to the name of the tavern, and also indicating that they served alcohol on the premises. The origin of these signs goes back to the Roman Empire, where tabernae would hang vine leaves outside to show that they sold wine – in England, as vine leaves are rare due to the climate, small evergreen bushes were used as a substitute, and that is why some of the earliest Roman taverns in the country used the bush as their symbol.

Until the 19th century, Constantinople’s licensed meyhanes made use of a similar technique. At the entrance was hung a rush mat – a sign that alcohol was sold on the premises. And next to the rush mat, you could often see an object hanging from the wall, which gave the meyhane its name. For instance, if a hammer was hanging from the entrance wall, the place would be known as the hammered meyhane. After the 19th century, as taverns were granted wider-ranging freedoms in conducting their business, they changed how they were christened and often bore the name of their owners.

A sales record kept by the qadi in 1663 shows what kind of an establishment a typical 17th-century meyhane was. The tavern was located in Kumkapı (on the northern shore of the Marmara Sea) and owned by a Rum called Hristo, and the sale included the following items: 70 casks of wine, 1000 glasses, 200 stools, 50 wooden trays, 40 pots, 2 large boilers, 20 trivets, 20 kebab trays, 300 spoons, and 1000 plates.

John Reid book, source: Amazon

Although some of the earliest descriptions of a meyhane date back to the 17th century, one of the most vivid depictions was given by Scottish traveler and journalist John Reid, who worked at a publishing house in London before visiting Constantinople in 1838. Reid starts his account by clarifying the city’s Muslim residents’ relationship with alcohol: “It is pure folly to suppose that Turks do not drink as deep as Christians. The Quran says a ‘Mussulman must not be seen drinking wine’ so they make sure they drink it without being seen.” He then tells the story of a hodja he knew intimately. Apparently, the hodja, who was quite fond of rakı and a believer in the literal reading of the scripture, would always turn his back to fellow drinkers in the meyhane he frequented to ensure he would never be seen taking a sip.

For Reid, meyhanes (which he calls winehouses) “come closest to the England tavern,” and during his two-year-long stay in the capital, he visited more than a handful of them. His favorite was a large meyhane (which means it must be licensed) in Galata and he provided a detailed account of the place, where he often observed Turks drinking alongside non-Muslims, particularly the Rum:

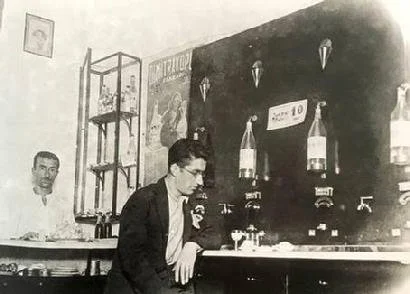

Ayakçı meyhanesi, source: istanbullite.com

“On entering from the street, you pass a courtyard where twenty to thirty parties of one, two, or three discuss their tipple, seated on their little stools around a circular board. Inside, the bar is a sort of wooden pulpit, from the cross beam of which are suspended great many glasses with handles, while at the end of the bench stand small rakee glasses. Round the walls and in the middle of the floor are small stools or settees about 20 centimeters tall. When anyone is inclined to have a tipple, a round board is put upon one of them, the tipplers draw their stools around, and wine is called not by the glass but by the liter. There is also a broad gallery running around the three sides of the chamber at about three meters from the ground, which is reserved for wealthier customers.”

Lavirentos-Galata, source: Istanbul Ansiklopedisi

That Reid’s favorite meyhane was in Galata is not surprising. Historically, Galata has been a cradle of meyhanes and according to author Ahmet Mithat Effendi, who was called “an infidel who lives to eat pork and drink rakı in meyhanes” by his rivals, Galata taverns’ fame goes all the way back to the 12th century. Indeed, meyhanes in Galata were different from their counterparts in other neighborhoods – meyhanes elsewhere were originally depots selling wine to non-Muslim urbanites and only in the 16th century, transformed themselves into taverns. Galata meyhanes, on the other hand, functioned as both stores and taverns from their origins. So famous were the taverns in the neighborhood that Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi noted: “Galata means meyhane.”

A Space for Male Bonding

Cornelis de Wael (Attr.) - Peasants smoking and drinking in a tavern, source: wikicommons

At least until the 18th century, London taverns remained male-only spaces. Beyond their formal status though, these were also symbolically male spaces in the sense that even when women were allowed in, they were often made feel unwelcome. Besides, their status in the taverns and pubs was fragile; even as late as 1982, pubs in England could refuse service to women merely on grounds of their sexual identity. Meyhanes were similar, if not worse. After the extensive modernization reforms of the second half of the 19th century, they could, in theory, go to a meyhane, and yet, they understandably refrained from doing so as they’d have felt even more uncomfortable than their counterparts in London. That is why they preferred spending time at beergardens and gazinos, accompanied by men, of course. Even the establishment of the republic did not change the character of the meyhane immediately, and it was only during the late 1940s that women (first a handful of authors followed by the general population) fully entered the world of meyhanes.

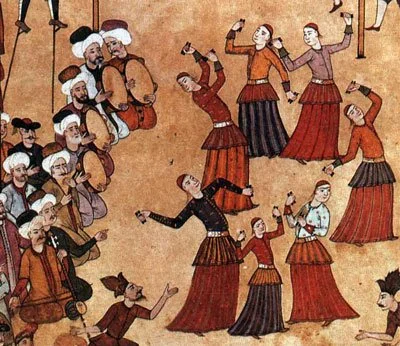

Kocek, source: Surname-i Vehbi

Meyhanes were not only male-dominated public spaces though; they were also spaces where men came to bond. The type of bonding in question here was beyond mere socializing – from the very early days, the meyhane space was characterized by the presence of homoerotic relationships, which categorically distinguishes them from the English pubs and signals a different form of masculine dominance of space. At the very heart of these relationships stood young, beautiful male dancers, known as köçeks, who almost exclusively came from the islands of Chios or Lesvos.

John Covel by Claude Laudius Guynier, source: wikipedia

John Covel, who was the resident priest at the British Embassy between the years 1670 and 1677, was flabbergasted when he first saw a köçek performance but still managed to keep detailed notes about the appearance of the dancer: He was a very young, beautiful boy who wore a silk dress embroidered with gold and silver. The torso area was very tight and transparent, and the light-colored skirt was wide and long.”

John Hobhouse, source: National Library of Scotland

John Hobhouse, another Londoner who traveled to Constantinople in 1809 was not pleased with what he observed from his private wooden gallery in a Galata meyhane floored with Dutch tiles: “Young boys – most are Greek but some are Jewish – danced to the music of guitars and fiddles. They were wretched young men and caused a few quarrels among the Turkish clients.” So abhorred was Hobson with the scenes he witnessed that, he concluded: “Rome itself could not have furnished a spectacle so degrading to human nature as the taverns of Galata.”

It wasn’t just the dancers that drew the clients’ attention though. Many waiters – again, mostly very young men from the islands of Chios and Lesvos – had their own followers. Perhaps the most famous of those was Küpeli Tiryandefil (Earringed Tiryandefil) who worked at Dodi’s Meyhane in 1883. Opened in 1875, Dodi’s was one of the most successful of the Galata taverns thanks in part to the wine Dodi brewed himself (with cinnamon and cloves) and in part to the beautiful waiters employed. And, Tiryandefil was by far the most stunning of them all. So much so that Aşık Razi, a famous Istanbulite poet, had written an ode to him: “Let me be your slave/Let me kiss your feet/Oh, beautiful Tiryandefil/Oh, beautiful rose of Galata.”

Unfortunately for Dodi, it wasn’t merely poets who fell for the young Greek man. The grandson of a member of the ulema very close to Sultan Abdülhamid II fell in love with him and spent all hours of the day at Dodi’s, returning to his family’s mansion drunk every night. The staff kept this a secret for a long time but one night, the grandfather heard the young intoxicated man sing: “Dodi’s tavern/The house of beauties/Tiryandefil with the gorgeous eyes/Is the one I’m in love with.” The next day, the old man told the Sultan what he saw and Abdülhamid issued a decree to shut down the meyhane and send Tiryandefil into exile.

Further Readings

Ahmet Mithat Efendi. Dürdane Hanım. İstanbul: İskele. 1882.

Ahmet Rasim. İstanbul’da Eğlence Hayatı. İstanbul: Maviçatı. 2017.

Daniel Goffman. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002.

François Georgeon. Rakının Ülkesinde: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’dan Erdoğan Türkiyesi’ne Şarap ve Alkol (14. - 21. Yüzyıllar). İstanbul: İletişim. 2023.

John Hobhouse. Travels in Albania and Other Provinces of Turkey. London: John Murray. 1850.

John Reid. Turkey and the Turks: Being the Present State of the Ottoman Empire. London: Robert Tyas. 1840.

Reşad Ekrem Koçu. Eski İstanbul’da Meyhaneler ve Meyhane Köçekleri. İstanbul: Doğan. 1947.