A City Awash with Pleasure Gardens

One of the first things that caught the attention of the travelers who made the long and arduous journey to Istanbul before the 20th century was the myriad of public gardens scattered all over the city and the Bosporus. As quintessential spaces of amusement, relaxation, and socialization, the pleasure gardens attracted thousands of Istanbulites from all walks of life. Promenading had always been a fundamental aspect of life in Constantinople, and these gardens provided the urbanites an opportunity to stroll around in pleasure, be seen and view others, enjoy the greens and the scenery, and feast, relax, and enjoy themselves in the fresh air.

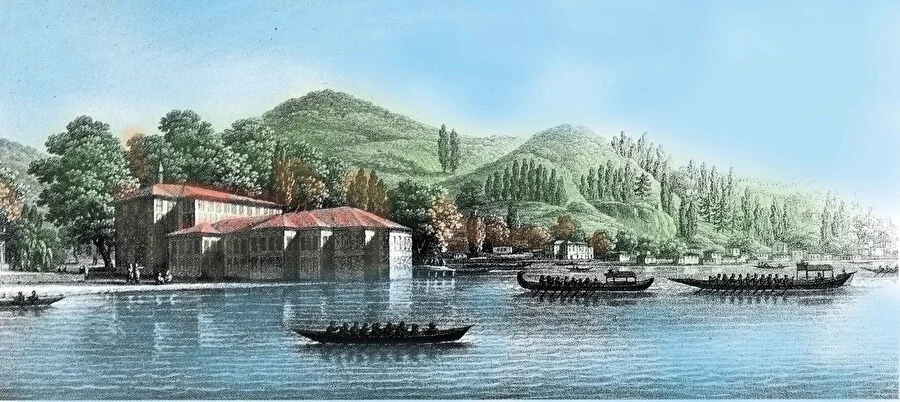

Küçüksu gravür, source: Thomas Allom, Constantinople

Each pleasure garden was renowned for its specific offering. For instance, the garden in Beşiktaş, located on the European shore of the Bosporus, was a favorite of bird lovers who would spend hours listening to the songs of golden orioles, blackbirds, horned owls, chaffinches, greenfinches, reedlings, and nightingales all nestling in large trees that cloaked the park. And, while the greens in Küçüksu on the Asian shore of Bosporus was the garden of choice for artists and men and women of letters living in villages nearby, the garden in Çırpıcı, situated on the Marmara coast, was chiefly frequented by artisans, shopkeepers, and gadabouts.

The slew of parks with diverse offerings and all within easy reach made pleasure garden crawling a favorite urban pastime. A group of Istanbulites would engage a caique for the day and have lunch in one pleasure garden, take their afternoon stroll in another, and have dinner in yet another before roaming the Bosporus for hours under the moonlight.

The Bosporus Gardens

Sunbeam RYS voyages & experiences in many waters, source: wikicommon

During her cruise of the Bosporus in her yacht during the mid-19th century Lady Annie Brassey was struck by the bright green vales, lining up the shores of the strait and carpeted all over with kaleidoscopic flowers. Particularly luring for locals and travelers alike were the Göksu and Büyükdere gardens.

Preaul - Goksu, source: Charles Pertusier, Promenades Pittoresques Dans Constantinople Et Sur Les Rives Du Bosphore

The Göksu pleasure garden, eponymously named after the river that fed it and lying at the northern end of the Bosporus on the Anatolian side, was a favorite recreation spot for princes and aristocrats before the 19th century. With the establishment of the public ferry system in the second half of the 19th century, the Göksu garden and river – dubbed the “Water of Life” by Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi – became more accessible and popular with the general public.

Julia Pardoe engraving, source: wikicommons

Julia Pardoe, second only to Lady Mary Montagu in all things Constantinople, thought Göksu was one of the few public places where Ottoman women could be themselves with no restraints: “If you want to see the Turkish women as relaxed as they are in their own homes, visit the beautiful Göksu valley on a Friday in a hot summer month. Sultanas recline on silk pillows with their veils tied a little less carefully. Elderly women lift up the lower part of their veil to smoke the pipes designed specifically for women. Younger ones look into the mirrors – the invariable companion of Turkish ladies – held up by female servants, having at least as much fun as the elders.”

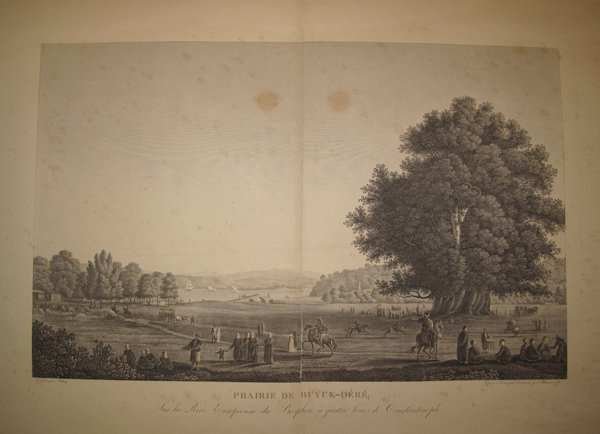

Büyükdere Çayırı-Melling, ource: Antoine Melling, Voyage Pittoresque de Constantinople et des Rives du Bosphore

Although Göksu’s popularity increased in the second part of the 19th century, Büyükdere remained the favorite pleasure garden of foreigners living in or visiting Istanbul until the First World War. During the Crimean War, British, French, and Italian soldiers stationed in Istanbul brought their families along and opted to live here rather than in the polluted, overcrowded Pera, transforming the borough into a socially vibrant, cosmopolitan space.

Located on the northern shore of the strait on the European side, where the Belgrade Forest and Bosporus met, Büyükdere, in Pardoe’s words, provided visitors with “breathtaking scenery.” The enormous, densely-leaved trees blanketed the meadow with vast patches of shade, which was, according to Evliya Çelebi, why the gardens were so popular with foreigners unaccustomed to the piercing rays of sunlight.

Where Wine Flowed Freely

It wasn’t only foreigners who attended the “after-hours” parties where the wine flowed freely.

In one of the far corners of the Göksu gardens, there was a coffeehouse called the Dört Kardeşler (Four Brothers), which offered its trusted habitués alcoholic beverages, including rakı and wine. Likewise, according to John Auldjo, who visited Istanbul in the first half of the 19th century, somewhere above the Büyükdere meadow sat a hotel, which sold “delicious London porters” to foreigners. But, according to Charles White, who spent three years in the capital between 1841 and 1844, real partying in pleasure gardens occurred in open air, after the sun went down.

During one of these parties hosted in an unspecified garden on the Bosporus, a fire was lit near a cypress tree to grill freshly caught fish. After devouring the delicious fish, the party reclined on the cushions laid on the carpets, chatting and smoking away the hours until sunset. When, at last, the night threw its veil around the meadow and the shore, and intrusive eyes could no longer watch the actions of Auldjo and his company, the wine started to flow, and the party sang and danced until the early hours of the morning.

Fenerburnu garden, source: Salih Erimez, Tarihten Çizgiler

And, it wasn’t only foreigners who attended these “after-hours” parties, according to White. In another gathering in Fenerburnu – on the Asian shore of the Marmara Sea – the Londoner joined a group of a few Englishmen, a couple of Persians, and a handful of Turks. Once again, they smoked, dined, and conversed until the sun descended. Then came out the champagne, and they drank for hours while admiring a Turkish effendi displaying his skills with the oud.

Kağıthane – Les Eaux Douces

“Not to have seen Kağıthane means not to have seen anything in this world.”

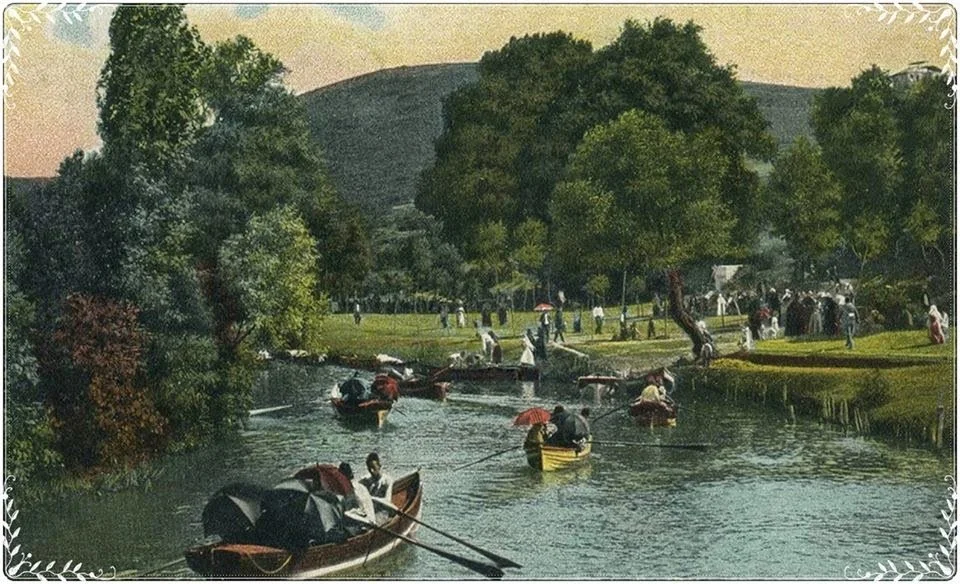

Source ottomanphotos.blogspot.com

Although Bosporus meadows became fairly popular in the 19th century, no other pleasure garden could match Kağıthane’s fame and beauty. Called the “Sweet Waters” by the Franks and located at the tip of the Golden Horn, Kağıthane remained Istanbulites’ favorite pleasure garden from the late 16th century all the way to the Young Turk Revolution of 1908. According to author Balıkhane Nazırı Ali Rıza Bey, one of the reasons why Kağıthane was so popular was its proximity to the city. Its location indeed made Kağıthane very attractive, but according to Evliya Çelebi, it was the experience that made one fall in love with the Les Eaux Douces.

Evliya Çelebi, source: biyografya.com

After hearing from one of his trusted companions that “not to have seen Kağıthane means not to have seen anything in this world,” Çelebi decided to visit the Sweet Waters with a group of close friends. So, he spent 40 pieces of gold on food (two sheep and other items), and a tent, which they set up under a tree by the riverbank. There were 3,000 tents erected on the meadows, making the garden look like the encampment of a marauding army. Throughout the two months he camped at Kağıthane, Çelebi especially enjoyed the nights when lanterns and candelas were lit, mellifluous sounds from ouds and qanuns filled the air, and dancers and fireworks entertained the crowds until the early hours of the morning.

Kagithane late 19 wikicommons, source: tarihteninciler.com

Çelebi was not alone in singing Kağıthane’s praises. Charles MacFarlane, who visited Istanbul in 1828, thought unlike Pera, which was “a bottomless pool of ennui”, Kağıthane was one of the loveliest spots in the capital: “Here I found, seated by the marble-lined sides of the canal, numerous Turks smoking their pipes and of women conversing and laughing with great glee and a few partaking in what we consider the masculine pleasure of puffing tobacco.” Likewise, Julia Pardoe enjoyed watching groups of Istanbulites scattered all over the meadow, feasting, drinking, laughing, and being entertained by Gypsy and Bulgarian musicians.

Enderuni Fazil-Zenanname-Kagithane-18yy, Source: Gzt.com

During Abdülaziz’s reign (1861-1876), Kağıthane became even more fashionable. The Sultan, a favorite with his subjects, would often appear on the balcony of the regal kiosk on the riverbank to the deafening cheers of the crowd. He kept hundreds of peacocks in the garden, which delighted Istanbulites and foreign visitors alike. According to Lady Brassey, the atmosphere was so relaxed during his reign that on a few occasions, she came across a group of Frenchmen enjoying wine and cold cuts while surrounded by Turkish parties on all sides.

Where There Are No Limits for the Lovers and the Beautiful

Fausto Zonaro Amusement at Göksu Google Art Project, source: wikicommons

Kağıthane had one indubitable and impregnable advantage over its rivals: any forbidden activity, including but not limited to sexual kind, could easily be concealed in its vast expanses – as the gardens could accommodate up to one-third of Istanbul’s population. That’s why, as early as the 17th century, Evliya Çelebi wrote, “There are no limits for the lovers and beautiful, fresh-faced youths swimming in the river at Kağıthane. The lover and the beloved wander around together, openly embracing. Day and night, they invite each other to their tents for feasting, conversation, or entertainment.”

Kagithane Pardoe, source: Julia Pardoe, Beauties of the Bosphorus

Many a foreign observers echoed similar sentiments. Take Baronne Durand de Fontmagne who stayed in Constantinople during the Crimean War. On his visit to Kağıthane he noted, “Ladies of Istanbul put on their best dresses and offer all of us a visual feast. Yashmaks are getting thinner and more transparent, making it possible to see and recognize the face behind them.” Likewise, George Townsend who visited Istanbul in 1875 wrote, “The Turkish ladies reclining on the cushions and taking their amusement in this meadow was one of the prettiest sights I came across in Constantinople.”

Charles Macfarlane by William Brockedon, source: wikicommons

Charles MacFarlane also had an exhilarating experience when he visited the Sweet Waters. As he was promenading with his local guide by his side, he happened upon a group of Turkish ladies, all in high spirits. As he passed them, he turned around in order to have another look, and one of them “showed her whole face instead of just the eyes.” He initially thought the wind might have blown off the yashmak, but lo and behold, “another mysterious covering was withdrawn.” And then, another. “Here were three charming faces really worth showing,” he mused and was about to make a move when his guide, ashen-faced with fear of what misfortune would befall them if he did, pulled him away.

The Temptation to Turn Turk

But no other Londoner enjoyed Kağıthane as much as John Auldjo did. Like his Istanbulite counterparts who admired the fair women of London roaming about in parks and streets, Auldjo spent hours in Constantinople’s pleasure gardens – especially Kağıthane – watching “beauties of Istanbul promenade and savoring every moment.”

Lespinasse-Kagithane, source: Ignatius d’Ohsson, Tableau Général de L’Empire Ottoman

“Kağıthane was the home to my happiest memories in the Orient.”

One evening, accompanied by a few of his friends, he met with a group of “exceedingly affable” Turkish ladies who lowered their yashmaks and effortlessly conversed with Auldjo and his companions: “They asked us about England, why we were in Constantinople, and then, finally, whether we found them beautiful. When we replied, ‘Absolutely’ (and we weren’t lying), they smiled heartily and offered us delicious ice cream.” Unfortunately for Auldjo, soon thereafter, “three old Turks came out of nowhere” and sucked all the joy out of the air. Yashmaks were pulled up and the women hastily signed Auldjo and his friends to leave. “Still,” wrote Auldjo, “Kağıthane was the home to my happiest memories in the Orient.”

On another occasion, on a warm June day, he chanced upon a Rum woman “whose breathtaking beauty eclipsed the charms of every other lady in the meadow.” When he returned to his lodgings he was still buzzing: “The ankle of the true Grecian race is remarkable for its exquisite symmetry…Her delicate small foot was chaussée in a neat black shoe, with a stocking of snowy whiteness. My language skills could not do justice to her beauty – she was like a peri descended from the celestial paradise.”

Auldjo book, source: internetarchive.org

Throughout his stay in Constantinople, Auldjo took every chance to meet and sometimes make portraits of women of Istanbul. One day, a close friend of his, Mdm. Giuseppino introduced Auldjo to a “stunning Turkish lady, a perfect specimen of Oriental beauty.” It took a lot of convincing, but in the end, she allowed him to draw her profile: “Her intense, black eyes. Her beautiful, flair complexion with the slightest tint of carnation suffused over the cheeks. Her lips! Those sweet lips!” Auldjo showed her the portrait, which she loved and when the time came for her to leave, “She put on her yellow boots over her beautiful foot and ankle, which it was a sin to conceal.” So ravishing were the women of Istanbul that Auldjo confessed, “It required immense self-discipline to resist the temptation to turn Turk.”

Further Readings

Charles MacFarlane. Constantinople in 1828: A Residence of Sixteen Months in the Turkish Capital and Provinces. London: Saunders and Otley. 1829.

Charles White. Three Years in Constantinople; or, Domestic Manners of the Turks in 1844. London: Henry Colburn. 1846.

George Townsend. A Cruise in the Bosphorus, and in the Marmora, and Aegean Seas. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1875.

John Auldjo. Journal of a Visit to Constantinople and Some of the Greek Islands in the Spring and Summer of 1833. London. 1835.

Julia Pardoe. The Beauties of the Bosporus. London: George Virtue. 1838.

Lady Annie Brassey. Sunshine and Storm in the East, or Cruises to Cyprus and Constantinople. London: Longmans. 1880.