A City Revamped

Istanbulites simply wanted to lead better lives – lives of which they’d heard from European travelers.

Kara-Kevi (Galata) and view of Pera, Constantinople, Turkey, ca. 1895 source: wikicommons

Karakoy in the late 19th century Sebah & Joaillier, source: wikicommon

Obsession is the right word to describe how 19th-century Ottoman rulers and Istanbulites felt toward Westernization. From literature to social treatises, from idle chatters in coffeehouses to parliamentary debates, Westernization was the predominant motif of 19th-century Ottoman public discourse. The rulers’ main concern was to help the empire recuperate and retain its rightful place among the leading nations of the time. Istanbulites’ desires were neither as noble nor as impossible to realize: they simply desired to lead better lives - lives of which they’d heard from European travelers, Levantines, their foreign neighbors, or read about in books and periodicals. And so came in an unstoppable tide of Westernization, the effects of which were nowhere felt as strongly as on social life and spaces where Istanbulites socialized.

Ostentatious Promenading – the Public Gardens

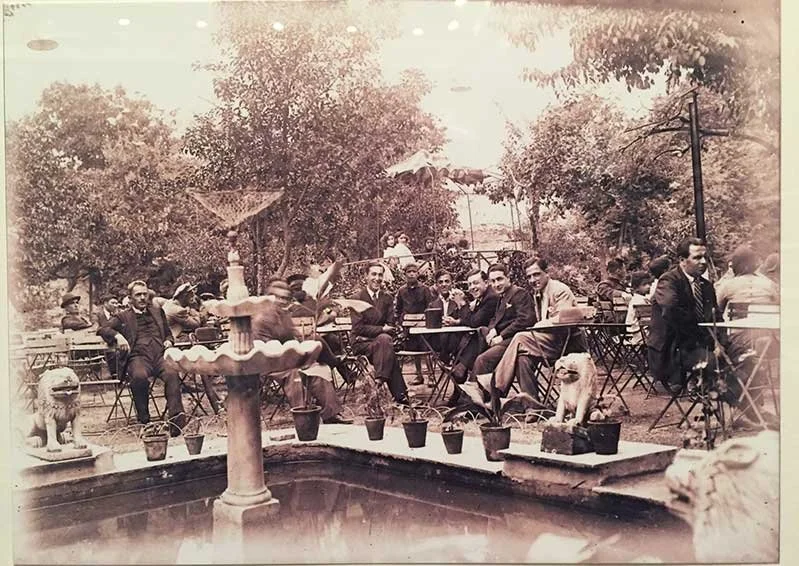

Tepebasi Garden, source: Kultur Istanbul

What distinguished these modern gardens from the traditional ones was that they were only public in name.

Promenading had always been a fundamental aspect of life in Constantinople, and the pleasure gardens scattered all over the city provided the urbanites an opportunity to stroll around, be seen and view others, enjoy the greens and the scenery, and feast, relax, and entertain themselves in the fresh air. These gardens, which were open to Istanbulites from all walks of life, continued to be popular with the urbanites until fin de siècle. However, by the mid-19th century, a new, different understanding of public gardens had already taken root among Istanbul’s elites.

What distinguished these new, modern gardens from the traditional pleasure gardens was that they were only public in name; in fact, their raison d’être was to keep the less fortunate members of the public out – hence, the entrance fee charged at the gates.

The plan seems to have worked to a T in the Çamlıca Gardens, located in Scutari, with amazing views of the Bosporus. The vast garden was divided into two separate sections: alla turca and alla franca. Habitués of the former included fat cats, chamberlains, aides-de-camp, and wastrels, who would enjoy rakı served in decanters and a variety of mezzes as they listened to the enchanting sounds of an oud. The alla franca section, on the other hand, was frequented by Levantines, non-Muslim locals, foreigners residing in Beyoğlu or Moda, and elite Turks. Beer was the drink of choice in this section, accompanied by gruyere cheese and red radishes. A modern European orchestra played tunes from popular operas and waltzes from sunset to midnight. The clientele in both sections – which, according to Lady Annie Brassey, included both men and women – were affluent members of the society and did not shy away from ostentatiously displaying their wealth – on the contrary, that was the very reason they made the long journey up the hills of Çamlıca in their sumptuous carriages and draped in the latest French fashion.

Garden Bar Tepebasi, source: oggito

Not every public garden was able to fend off the less-well-to-do Istanbulites. Tepebaşı Gardens, located at the heart of Pera, also charged an entrance fee, and yet, thanks to its easily accessible location, lower classes didn’t need to rent a carriage or caique to reach there. According to historian Reşat Ekrem Koçu, having paid the entrance fee, “the poorer clients including, foremen, shipmates, and apprentices” would stroll around the park for hours at an end while their wealthier counterparts – and especially pashas, beys, and foreigners – sat at cast iron tables and enjoyed local Bomonti beer at a hefty price.

If You Are Not Welcome at Ballos, There Is Always the Baloz

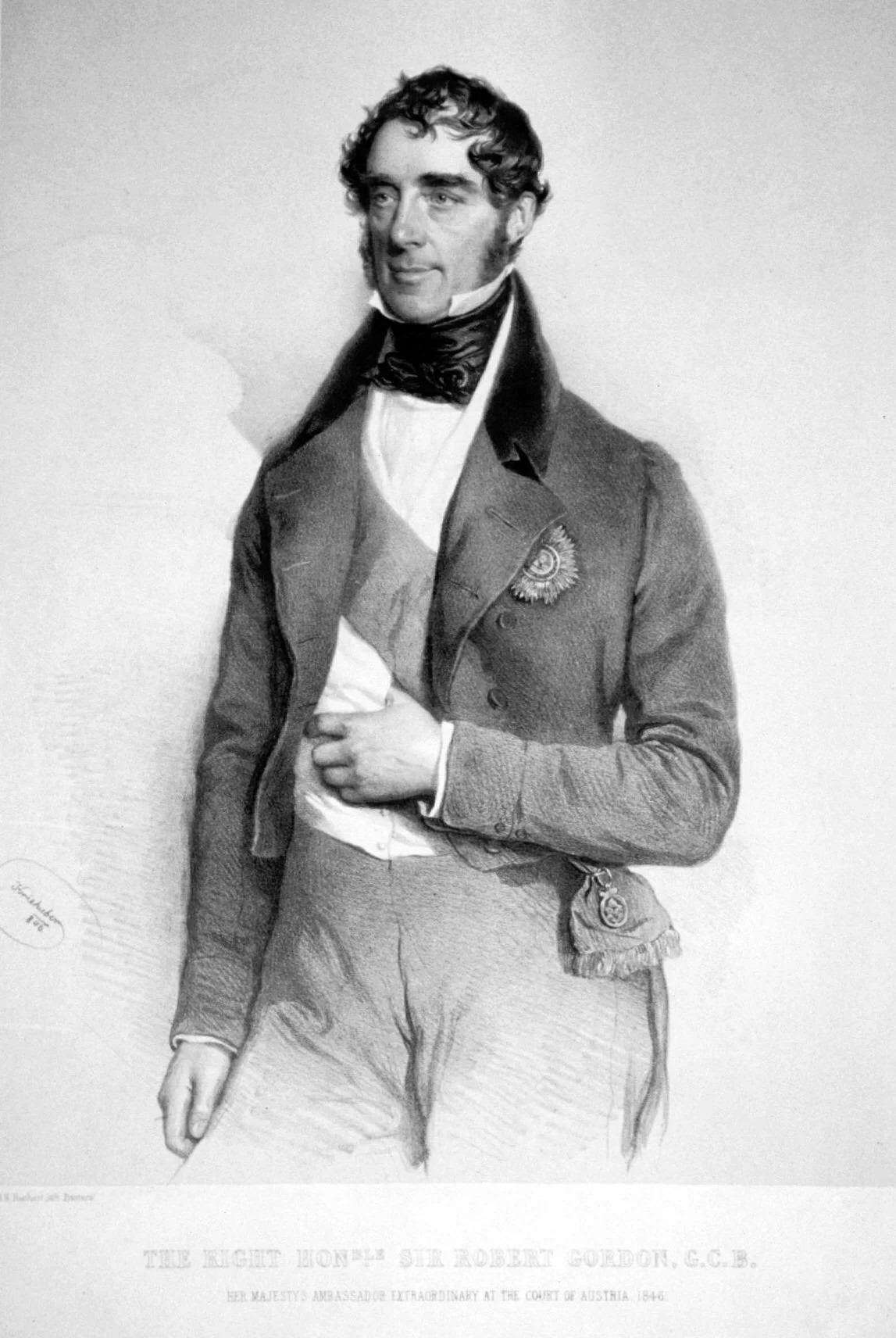

Robert Gordon, source: wikicommons

The British Ambassador, Sir Robert Gordon, hosted the first official ball in Constantinople in 1829. According to the Chronicles of Abdülhak Molla, the event, attended by both men and women, was held at a British frigate, and among the distinguished guests were the Minister of Defense, the Grand Admiral of the Navy, and the Sultan’s private barista. Shortly afterward, other embassies followed suit, hosting balls and garden parties at every chance.

Soon, the ballo – in Istanbul, irrespective of the host, the Italian word was used to describe these events – became the talk of the town. In coffeehouses, pleasure gardens, and meyhanes, Istanbulites talked, gossiped, and often speculated about how men and women were getting together at parties, singing, dancing, drinking, and laughing away the hours until the sun appeared from the horizon. What emerged as curiosity soon gave way to jealousy, as it often does, and Istanbulites began, first in whispers but then with ever-increasing boldness, their desire to attend these ballos. That was out of the question of course, as these events were reserved for a select few – yet, a few entrepreneurs pondered: can the people not have their own ballos? And that is how the baloz was born.

The baloz owed its initial popularity to the presence of women inside.

Hotel D’angleterre, source: fotokart

The first baloz was likely opened at the beginning of the 1840s in Tophane, bordering the Genoese quarter to the south. In merely a decade, the borough was swarming with these “original bars of Istanbul.” So, the elite ballo that men and women invitees attended, transformed into a more accessible, open-for-all establishment, the baloz, where men were clients and women worked – as waitresses, bartenders, dancers, singers, and hostesses.

A typical late-19th-century baloz was Arap Todori’s in Galata. It consisted of a spacey saloon with a big oil lamp hanging from the ceiling and smaller ones adorning the walls. Marble top tables lined up three sides of the large room, and on the fourth stood a stone counter, where the owner Todori, a Rum with an uncharacteristically dark complexion – “hence, the nickname Arap,” notes historian Sermet Muhtar Alus – invariably hung out. At the center of the saloon was a raised platform for the orchestra, which comprised a clarinet, lute, djembe-djembe, and tambourine. Beer was the choice drink for the clientele, most of whom were foreign sailors, local grocers and porters, and young Turks who had recently fallen in with beer and who sat and conversed with the hostesses in their colorful shirts and skirts but categorically refused to dance with them.

The baloz owed its initial popularity to the presence of women inside – for the first time in the history of the Ottoman Empire, men and women socialized and entertained themselves by singing, dancing, and drinking in the same space without fear of reprisal. However, soon balozs started to lose their regular customers due to violent brawls that recurred night in, night out. Such was the infamous nature of the balozs by the last decade of the century that an official document referred to them as “Ümmü’l Habaset,” meaning the mother of all evil. Fortunately for Istanbulites, two other types of establishments offering alla franca entertainment had already emerged in Constantinople.

Entertainment, French Style – the Café Chantant

Café Chantant, a.k.a., café-concert or caf’conc, was a kind of musical establishment associated with the Belle Époque. The first café chantant in Paris was established in 1789 on the Champs-Élysées, and after less than a century, there were tens of them scattered all over Pera in Istanbul. Foreign orchestras and singers – often French – attracted Istanbulites who yearned for light-hearted entertainment but avoided the balozs for fear of being swindled or even robbed.

Café Flamme, source: kahvve.com

The most famous café chantant in Istanbul was called Café Flamme. Located on Grande Rue de Péra and owned by a gargantuan Levantine, Café Flamme was fashionable among the wealthy Istanbulites and foreigners visiting the city. Rakı, gin, and cognac were the most popular drinks, and the café also offered a wide range of food options such as caviar, tongue, smoked swordfish, goose eggs, ham, and kashkaval cheese. Turkish author Ahmet Rasim recalls only French being spoken in the café whose waiters were so gentlemanly that “one would feel embarrassed when ordering food or drinks.”

Punch store, source: eskiistanbul.net

Another novelty that made its way to the Ottoman capital in the 19th century was the punch. Introduced to Istanbulites by British sailors and travelers, the punch was a cocktail made of rum, water, sugar, a variety of spices such as ginger and bergamot, and fresh fruits. Although initially offered in cafés chantant, these cocktails became so popular with the locals that specialized punch stores cropped up all over the city in the second half of the 19th century. Soon, confectionary shops jumped on the bandwagon, offering an alcohol-free version alongside the original punch. Punch had become so fashionable a drink by the last decade of the century that meyhane owners, unhappy with the presence of yet another player in the entertainment market, petitioned the government to ban the opening of new punch stores whose number had already reached a thousand.

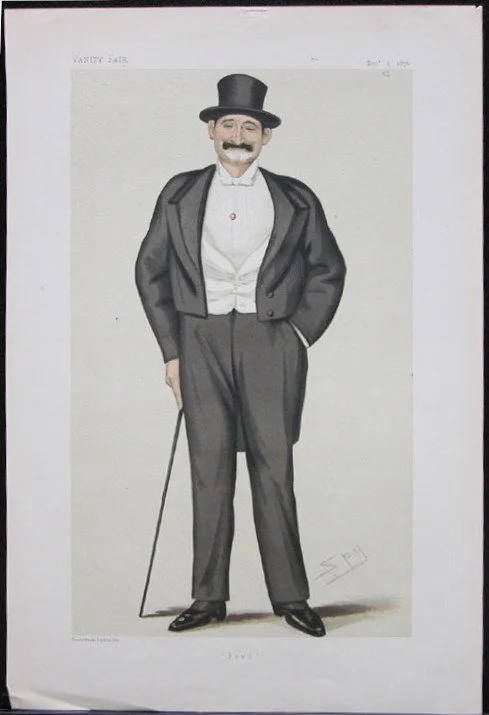

The only British traveler who wrote about the cafés chantant in Istanbul was Frederick Burnaby

Frederick Gustavus Burnaby, Vanity Fair, 1876-12-02, source: wikicommons

Although they were popular with foreigners, the only British traveler who wrote about the cafés chantant in Istanbul was Frederick Burnaby, who visited Constantinople and stayed in the Hotel de Luxembourg in 1876. One night, a Turkish friend of his took him to a café chantant in Beyoğlu where “stern-faced Turks were smoking nargile and a handful of Rum were discussing world affairs.” Later, a French singer adored by the Turkish customers took the stage and sang a song about the dethroned Sultan Abdülaziz. Burnaby was particularly impressed with the beautiful Italian and Hungarian waitresses and when chatting with the owner, found out that he never hired “average-looking women because Turks only came here to watch the waitresses.”

Pera, source:kahvve.com

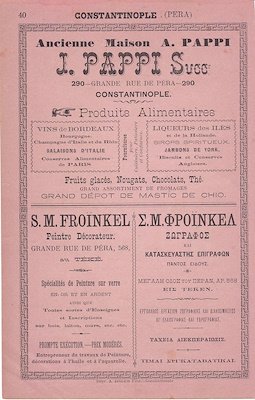

Pappi’s leaflet, source: Levant Antika

Right across the Café Flamme, on Grande Rue de Péra, no. 290, stood a corner store called Pappi’s. Famous for its Bordeaux wines, Dutch liquors, French champagnes, and Russian vodkas, Pappi’s was much more than a corner store. According to Ahmet Rasim, less-well-to-do Istanbulites would start the night at Pappi’s, drinking a few glasses of rakı or beer in quick succession before making their way to expensive establishments like the cafés chantant.

Entertainment, Grand Style – the Gazino

Reputability constituted the essence of 19th-century gazinos in Constantinople.

Of all the new, modern establishments that made their way into the Istanbul entertainment scene in the 19th century, gazino was undoubtedly the most glamorous. Gazino came from the Italian word casino, which might mean a small country villa, a summerhouse, or a social club. The first gazino in Constantinople was established at the beginning of the 19th century, and the reason they have been able to play a prominent role in Istanbul’s social life well into the second half of the 20th century has been the emphasis on reputability.

An official document dating back to the mid-19th century states, “There is no harm in Muslims with high social standing to go to gazinos as unlike meyhanes, these are reputable establishments.” Indeed, the respectability of the establishment and its clientele constituted the focal point of debates about the gazino from the 19th century onward. Gazino owners had to show extreme caution regarding who they admitted to the premises and were required to keep meticulous records for each and every one of their customers. They had to ensure no undocumented persons were allowed inside, that no one gambled inside, and most importantly, that no brawls or other sorts of mischief occurred in their establishment. Only then were they able to acquire or renew the gazino license.

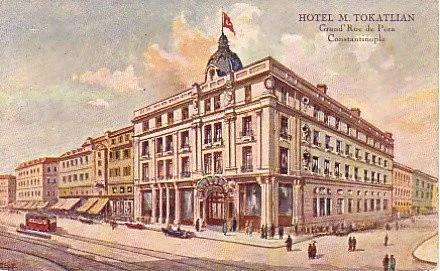

M. Tokatlian Hotel Pera Grand Street Constantinople [Istanbul], source: wikipedia

Istanbul’s gazinos were kept under strict police surveillance at all times. The state was concerned with the identities of the clients, who they conversed with, and about what. Tokatlıyan Hotel’s gazino was of particular interest as its clients included both locals and foreigners. During the final years of the 19th century, Keeper of the Imperial Wardrobe, İlyas Bey would spy in the gazino every evening, taking mental notes on who socialized with whom. In another incident in 1820, while drinking at Vasil’s in Beyoğlu, two Frenchmen and one Croatian had raised their glass in honor of the Russian Emperor, leading to their prompt arrest by the police officer Murat Efendi, who was the “undercover agent on duty.”

The other defining characteristic of the gazinos was the grand style of entertainment they offered – large, European-style orchestras, foreign and local singers, delicious food, a wide variety of alcoholic beverages, and dancing were all part of the 19th-century gazino experience. Gazino habitués included Istanbulites of all nations, religions, and genders, as among the patrons of gazinos, a considerable number were women.

View of Galata Bridge in 1895, source: wikicommons

Besides the ones at the heart of Pera and Galata, there were three other types of gazinos in 19th-century Istanbul: pier gazinos, country gazinos, and rail station gazinos. The most famous pier gazino was in Fener. According to the poet Aşık Razi, wealthy young Turks would drink here before jumping on their caiques to join the crowds at Kağıthane pleasure gardens. Country gazinos, many of which were in the Princes’ Islands, were modest establishments with a few tables shaded by the trees. As indicated by their name, rail station gazinos were situated next to train stops. The best-known of these was in Maltepe, on the Asian side of the city. Customers would bring rabbits, woodcocks, and quails they’d hunted in the surrounding forest, have the owner Andriko prep them for the evening, and share them with the rest of the clients.

One of the most renowned 19th-century Pera gazinos was Arkadi’s. Run by a retired police chief called Arap Enver, Arkadi’s was a spacey saloon with a platform for orchestra in one corner and a dancing area in the middle surrounded by marble-top tables lining up the walls. The blue ribbons hanging from the high ceilings created a sensation of standing and dancing inside a cascade. Arkadi’s was also where bingo was introduced to Istanbulites during the Crimean War. Following the First World War, the gazino became a favorite with White Russian emigres, whose dance shows – particularly foxtrot – attracted British and French soldiers stationed in the city.

Further readings

Ahmet Mithat Efendi. Letaif-i Rivayat. İstanbul: Çağrı. 2017.

Ahmet Rasim. İstanbul’da Eğlence Hayatı. Istanbul: Maviçatı. 2017.

Ahmet Rasim. Şehir Mektupları. Istanbul: İskele. 2016.

Fred Burnaby. On Horseback Through Asia Minor. London: Sampson Law, Marston, Searle & Rivington. 1877.

Lady Annie Brassey. Sunshine and Storm in the East, or Cruises to Cyprus and Constantinople. London: Longmans. 1880.

Sermet Muhtar Alus. Onikiler. Istanbul: İletişim. 1999.