Istanbul, the City of Plenty

Almost every traveler from all corners of Europe mentions, at least in passing, the wide variety of delicious edibles available in Istanbul. However, it is Charles White who, by virtue of residing in the capital for three years, paints us the most lucid picture of the unrivaled assortment and plentitude of the victuals Constantinople offered.

Fruit Sellers by İntizami, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Like many of his fellow Londoners, White’s attention was first grabbed by the plethora of fruits available – likely because of the relatively striking lack of choices in his hometown. Even the lowest classes, he awed, had access to oranges, lemons, figs, melons, watermelons, and last but certainly not least, grapes, which “were among the best he’d had in his life” – a sentiment echoed by Richard Snow. Less common and yet still more in abundance compared to London were quinces, plums, pomegranates, strawberries, mulberries, cherries, peaches, apricots, and pears.

Fruit Vendor by İntizami, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Vegetable Vendor by İntizami, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Vegetables were not to be overshadowed. White admitted it would have been impossible to walk his readers through all the city had to offer in this department. However, he could not not mention a few scrumptious items he frequently enjoyed during his three-year-long stay: artichokes, often served with a rich, creamy sauce; small, unbleached lettuce so tasty that people bought and consumed on the streets; raw and pickled cucumbers; the “extraordinarily huge” cauliflowers; and, aubergines, which “Europeans struggled with, but locals – Muslim and non-Muslim alike – could not do without.”

Legumes, 1920s, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Another edible that drew the attention of travelers was legumes. Although White merely mentioned broad and kidney beans as tasty options, fava beans, green peas, lentils, and lupins were also enjoyed by locals and visitors alike. Indeed, such was the place legume occupied in the city’s culinary culture that Athanasius I, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 1289 to 1293 and from 1303 to 1309, referred to Byzantines as kyamafagoi – legume eaters.

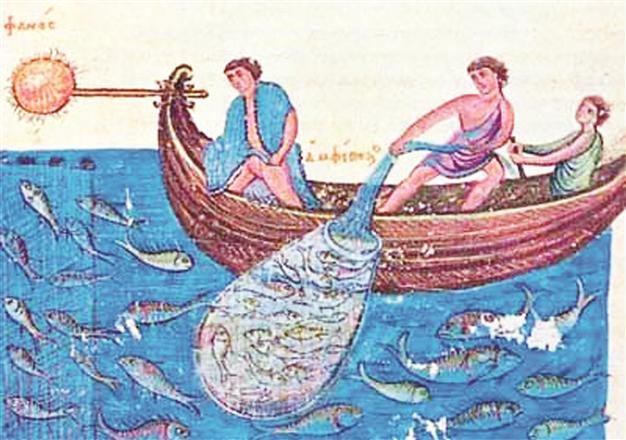

A Plethora of Fish

Fishing by Şükr-i Bitlisi, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Although they were impressed with the healthy fruits and vegetables available in the capital, what truly dazzled travelers was the abundance of fish in the city’s surrounding waters. Pierre Gyllus, Edmondo de Amicis, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, Baronne Durand de Fontmagne, and Leon Trotsky – exiled in Istanbul between 1929 and 1933 – all praised the delectability of Constantinople’s fish. However, it was once again Charles White who provided us with the most detailed account of the fish the city’s waters are teeming with.

Left: Fishermen by Lokman, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi, Right: Fish Seller by İntizami, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Market by Melling, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

“The extraordinary beauty of colors observed in some varieties is highly interesting; green, gold, pink, azure, red, and silver glisten in brilliant tints upon their scales,” wrote White and proceeded with a list of Istanbulites’ favorite fish, most of which he added “were foreign to British markets.” The following is an excerpt from the said list.

Red mullet. “Worthy of its reputation among Roman gourmands.”

Bonito. “Tastes amazing when caught in October. A portion is eaten fresh, but the greater part is cut up, salted, and preserved in casks.”

Sea bass. “Its white flesh is delicate and firm. Europeans boil it whereas Turks cut it up and dress it with vegetables.”

Swordfish. “Has an exceedingly good flavor, especially when caught in November as it remigrates from the Black Sea.”

Sea bream. “Its flesh is esteemed for its light and wholesome quality.”

Bluefish. “Rarely met in waters other than those of Bosporus and Marmara. Its flesh is extremely delicate and more esteemed than any other fish frequenting the neighboring channel.”

Fishing in Byzantium, source: rearview-mirror.org

Charles White included Bosporus’s mussels and oysters among the most delicious seafood he has tasted in his life and noted that Muslims refrained from consuming them in accordance with Mahomedan law. Likewise, Baronne Durand de Fontmagne claimed Muslims did not touch crustaceans for religious reasons. However, according to an anonymous 17th-century traveler, the reason Turks avoided crustaceans was not religious but palatal: “Turks like their dishes well-cooked. That’s why they enjoy eating all sorts of fish but stay away from all crustaceans.” And, he was likely correct as, by the mid-19th century, following drastic changes in the city’s culinary culture, mussels had already become a key component of Istanbul’s cuisine.

The Gentle Art of Levantine Cooking

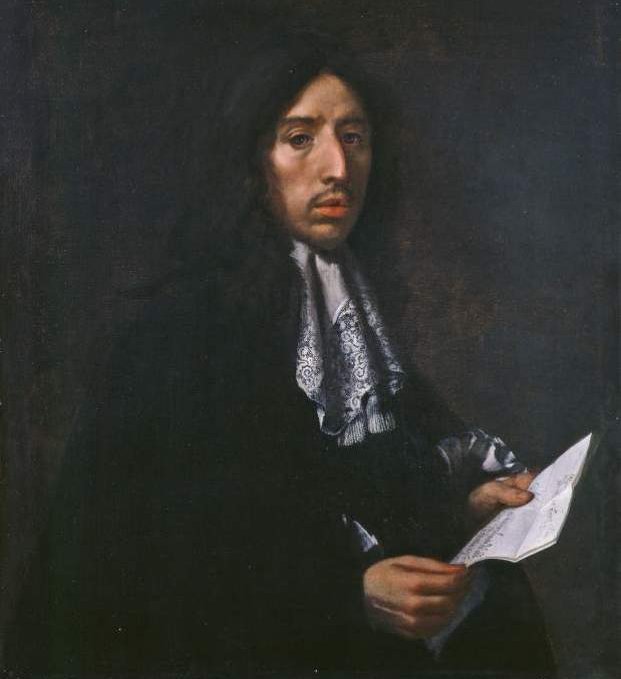

John Finch by Carlo Dolci, source: wikicommons

In his ambassadorial memoir, John Finch wrote: “Greek, Italian, and Turkish masters had combined for centuries to bring the gentle art of Levantine cooking to a height of perfection that only the Archimagirus of Zeus could have excelled.” And he was absolutely right in pointing out a continuity between Byzantine and classical Ottoman cuisines.

Feast for Ulema by Vehbi, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Most of what we know about Byzantine cooking comes from medical books and poems, and from those, we can ascertain that soup eaten with bread was the most commonly enjoyed dish in the Empire. A favorite soup recipe included water, onions, salt, oil, and marjoram among its ingredients. Often, legumes were added to make the soup more filling. And, to turn the dish into a stew meat (lamb and not beef was the choice cut) or fish (dry or fresh) were added into the mix.

Ottoman Feast by İntizami, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

In his satirical poem about life in Byzantium, Ptokhoprodromos (Prodromos the Beggar) listed the ingredients of a perfect stew: cabbage, eggs, Cretan cheese, curd, garlic, onions, pepper, oil, and a selection of dried and fresh fish. To ensure that the stew was savory enough, the beggar added, the mixture needed to be cooked not in water but wine.

Ottoman cook by Gouffier, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Soup occupied a crucial place in classical Ottoman cuisine as well. One of the most popular soups from the 15th century included parsley, cucumbers, courgettes, plums, and unripe grapes among its ingredients. Meat – like their Byzantine predecessors, Ottomans also preferred lamb over beef – and pilaf – bulgur for the lower, and rice for the upper classes – constituted the two other components of a typical classical Ottoman meal.

Evolving Tastes, Changing Habits

Restaurant, 1920s, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

The 19th century ushered in sweeping sociocultural change focusing primarily on the Westernization of social life, cultural practices, and political institutions. Among the countless new establishments that appeared in this era of unprecedented transformation was the lokanta – coming from the Italian word locanda, meaning an inn providing food and lodging for travelers. These were the first modern restaurants in Constantinople, and their complexion was unmistakably European.

Restaurants in the sense we understand them today did not exist in Istanbul during the Classical Age. There were establishments that sold food to shopkeepers and singles, run by cooks who were part of a guild. There were no chairs or tables on the premises, which worked on a principle similar to modern “takeaway restaurants.” Customers who bought the meal that often consisted of chickpea soup, boiled meat, and pilaf, ate it in gardens or on the streets. The aim was not to enjoy food but to fill it up.

The most fashionable lokantas were the ones that combined culinary pleasures with an alluring atmosphere.

Restaurant in Karaköy, 1920s, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

The lokantas’ concern was not functionality but ambiance and enjoyment. These provided a Western-style dining experience with tables, chairs, and cutlery – and, they all offered cosmopolitan menus and alcoholic beverages, especially wine. However, unlike in traditional taverns, a.k.a. meyhanes, where drinks were primary, in lokantas food was primary and alcohol supplementary. Their European complexion was reflected in their names as almost all of the lokantas opened in the 19th century had foreign names – even the famous Abdullah Effendi, established in 1888 in Galata, was initially called Victoria’s.

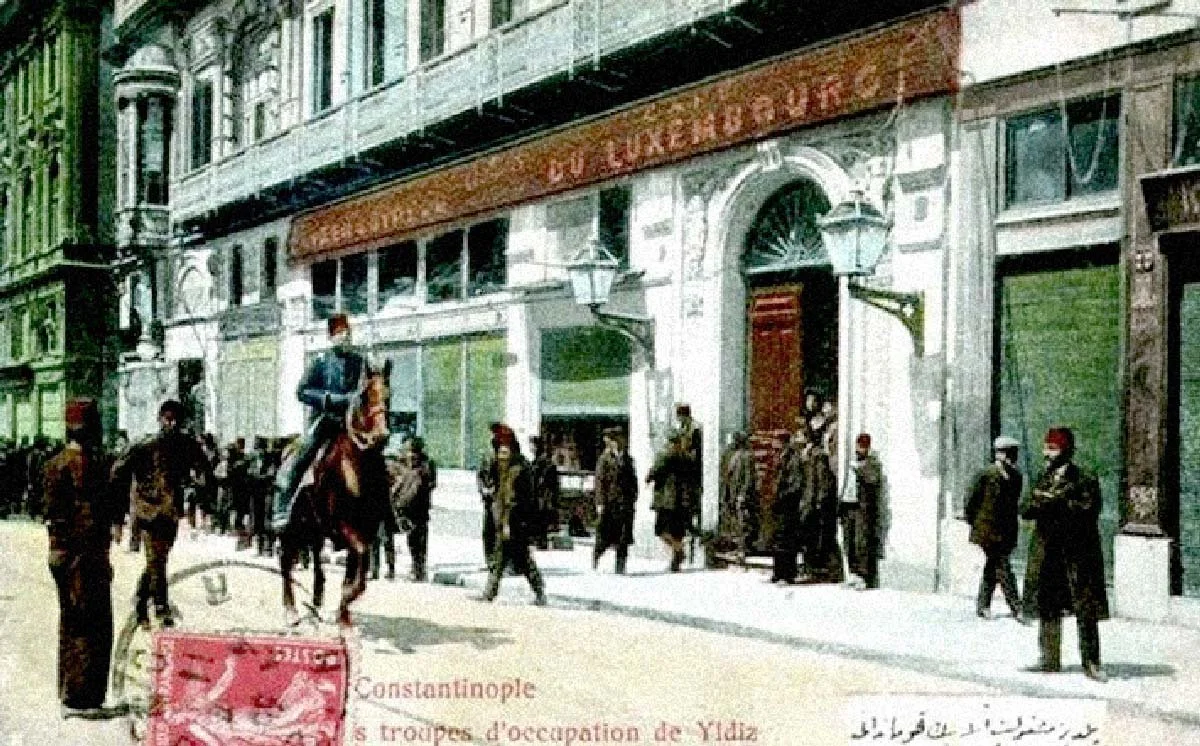

Cafe Luxembourg, source: wikicommons

The most fashionable lokantas were the ones that combined culinary pleasures with an alluring atmosphere. Hotel de Luxembourg’s restaurant was famous for its succulent perdrix aux truffes (partridges with truffles) and flavorful vol-au-vent à la financière (canapes with financière sauce), but it also offered “views” of Istanbulites promenading the Grande Rue de Péra. Pavlick’s in Asmalımescit (near Galata), the choice restaurant of men and women of upper standing, provided the highest quality foreign beers alongside breathtaking views of the Bosporus.

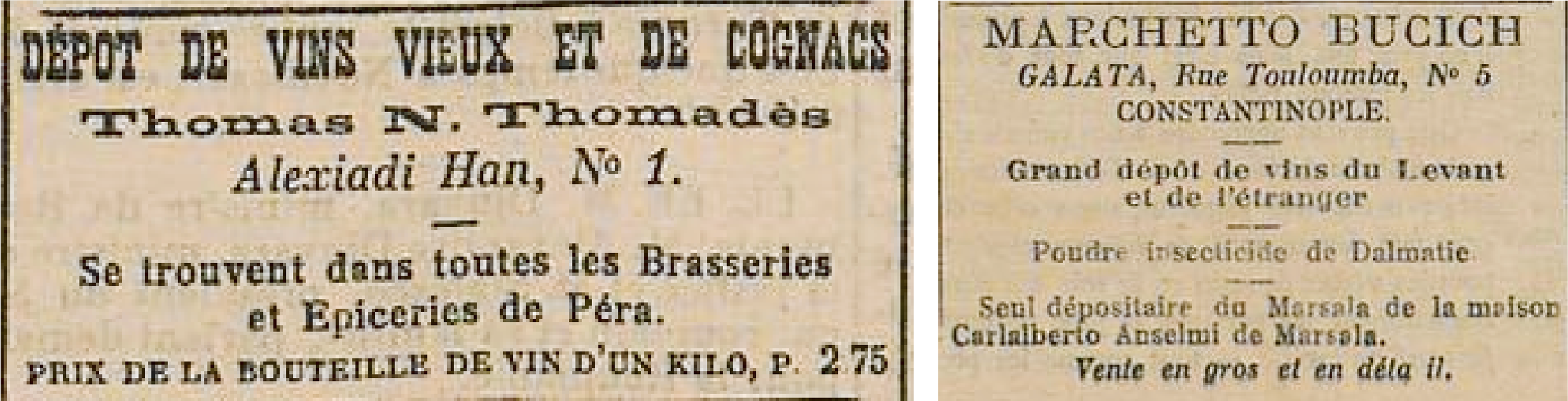

Left: Thomades Liquor Store, 1987, source: Le Moniteur Oriental, Right: Bucich Liquor Store, 1987, source: Le Moniteur Oriental

19th-century Pera swarmed with stores that sold foreign food and beverages. According to John Auldjo, amongst these, Mr. Stampa’s Emporium was in a league of its own. “Adrianople tongues, Yorkshire bacon, Scotch whisky, French cognac, Scotch ale, London porter, and English cheeses can be obtained at the right price. In fact, in no city on the globe can you obtain domestic and foreign luxuries as plentifully as in Constantinople.” Charles White was also a regular at Mr. Stampa’s where he bought London porter and Burton ale. What amazed him about the warehouse though was its social character: “This is a resort of suburb quidnuncs, who drop in to hear the news and discuss the rise and fall of prices and pashas.”

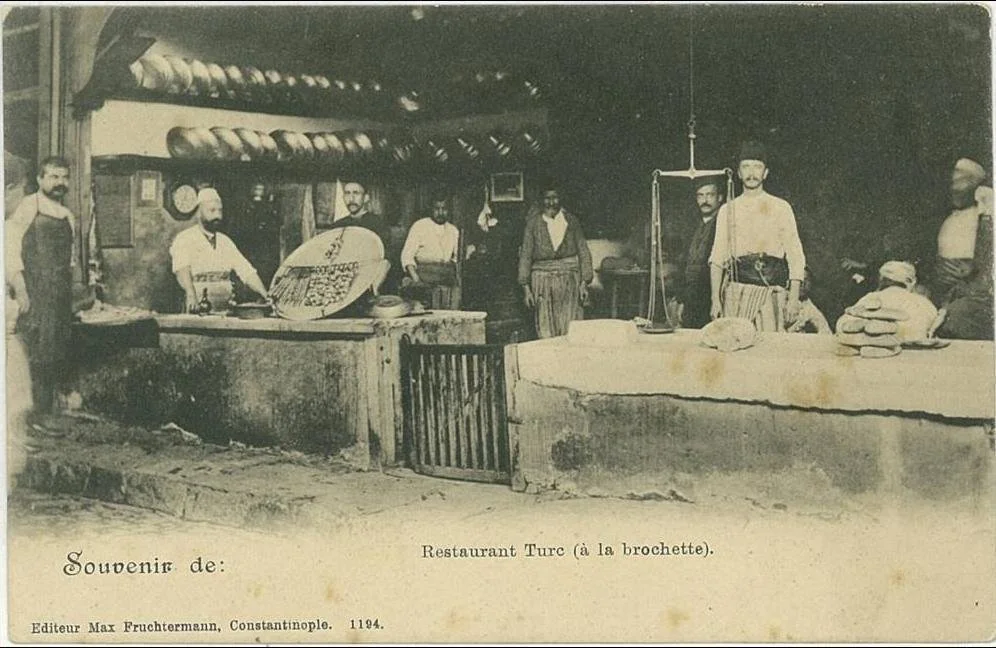

Making Kebap by İntizami, source: Büyük İstanbul Tarihi

Despite the proliferation of modern lokantas in the 19th century, kebab restaurants continued to be the primary culinary attraction for travelers visiting Constantinople. There are countless travelogues describing how kebab was prepared and eaten in Istanbul but, once again, it is Charles White who delivers the most vivid description.

Kebap Restaurant, Istanbul, 19th Century, Photo by: Max Fruchtermann, source: geneanet.org

The restaurant was located on the southern side of Divanyolu Street near the ancient Hippodrome. It was, in White’s words, “the most celebrated kebab store in Constantinople” and many a foreigner “had offered huge sums to persuade its owner Hacı Mustafa to move and open a kebab restaurant in their hometowns” – all to no avail. The open front of the restaurant was “ornamented with a clean marble counter on which rest fine lettuces, bowls of yogurt and famous Eyüp curd, skewers of mutton, giblets for making soup, rice for pilafs, sheep’s head and trotters for various dishes, fat fowls for stewing and roasting, courgette and vine-leaf dolmas, and pickles.” Inside, the walls were furnished with shelves full of handsome China bowls, cups, and glasses. From the ceiling were suspended quarters and halves of (not overfat) muttons and slow charcoal fires kept on burning on stoves. While “commoners” sat and ate on stools placed on a platform at the center of the huge room, “persons of higher standing were taken to an airier and cleaner gallery above.”

White and his companions enjoyed a forest kebab prepared by placing a whole lamb in a hole in the ground in a deep earthen dish, covered with burning embers. The outcome, in White’s words, was a work of art: “Stuffed with currants, almonds, and pistachios, the lamb could not be surpassed in flavor by the most succulent roasts, for which our islands stand pre-eminent.”

From Incorrigible Drunkards to Social Drinkers

Once bairam arrived, Turks made themselves amends in gluttony, drunkenness, and lust.

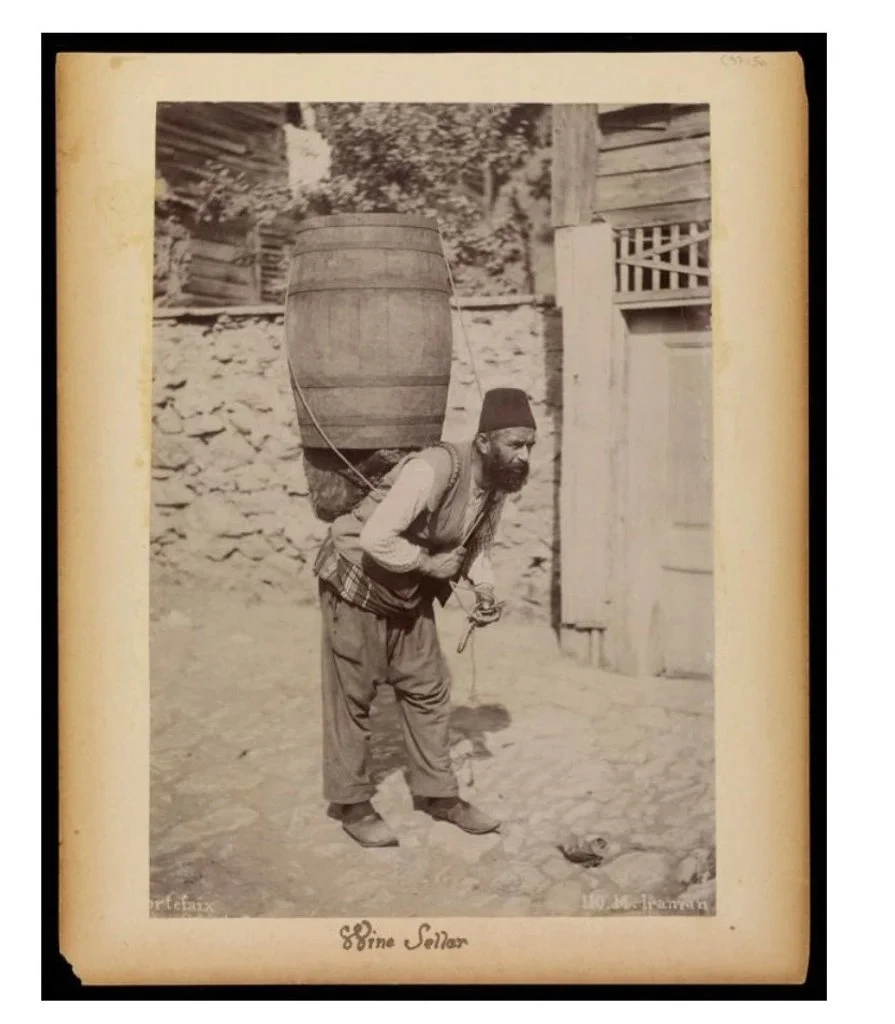

wine sellers, source: winesofa.eu

That Muslims in Constantinople enjoyed wine as much as their non-Muslim neighbors was one of the worst-kept secrets of Ottoman history. For instance, Henry Blount, who visited Constantinople in the 17th century noted that not only Janissaries but all Turks drank wine. He noticed that Ramadan was an exception when they strictly observed the rules, but once bairam arrived, “they made themselves amends in gluttony, drunkenness, and lust.” As John Hobhouse rightly pointed out, “The use of wine is prohibited by Mahometan law but it depends on the humor of the reigning Sultan whether this article should be strictly observed.”

wine seller, source: winesofa.eu

Many Turks were, in secret, decided worshippers of wine.

So, what shocked the visitors to Constantinople was not that Turks and Muslims drank wine but the lack of moderation with which they did. “As no Turk is a drinker without being a drunkard, I was witness to as much excess in this respect, as might be seen in the West end of London,” wrote Hobson in 1809. John Auldjo also noticed, as late as 1833, that “many Turks were, in secret, decided worshippers of wine” who simply could not comprehend the idea of “enjoying a social glass.”

La Regence by Aleksandr Kozmin, source: Metromod.net

However, things began to change in the second half of the 19th century. And once again, it was the Crimean War that served as a catalyst for change. With the arrival of French and English soldiers and their families in the city, Istanbulites were introduced to dinner parties that men and women attended together, and where wine and other alcoholic beverages were consumed without restrictions. As Robert Walsh observed, Turks had started to drink wine in their homes and become capable of limiting themselves to a few glasses, enjoying the Dionysian drink rather than trying to get drunk with it. This was also when, drinking alcohol publicly but in moderation was beginning to be seen as a symbol of civilized, European conduct. And it was not long before a new Istanbulite figure, cast in that mold, began to play the leading role in the city’s entertainment life.

Further readings

Charles White. Three Years in Constantinople; or, Domestic Manners of the Turks in 1844. London: Henry Colburn. 1846.

G.F. Abbott. Under the Turk in Constantinople: A Record of John Finch’s Embassy, 1674-1681. London: Read Books. 2018.

Henry Blount. A Voyage into the Levant. London. 1636.

John Auldjo. Journal of a Visit to Constantinople and Some of the Greek Islands in the Spring and Summer of 1833. London. 1835.

John Hobson. A Journey Through Albania and Other Provinces of Turkey in Europe and Asia, to Constantinople, During the Years 1809 and 1810. London: Cawthorn. 1813.