A city of idleness, endless pleasures, and sweet tastes…oh, and dogs

However unpleasant, interminable, and exhausting their journey was, the moment their vessel entered the Bosporus, travelers – without exception – felt overwhelmed by the beauty of Istanbul. Such was the “unequaled loveliness” of the panorama that appeared before him when Albert Smith’s ship slowly glided into the Golden Horn in 1850 that the “feelings of wonder and admiration became absolutely oppressive.” In fact, he had only been moved like that once before, “when I looked down upon London, by night, from a balloon.”

Thomas-Allom-Constantinople from the Entrance of the Golden Horn

However, after disembarking at Galata – the Genoese quarter – and making their way into the heart of that picturesque view, they were overcome by a feeling of letdown at least as powerful as the astonishment they felt minutes ago. The narrow, cobbled streets that snaked through the gloomy, dilapidated houses and the terrible reek rising from heaps of filth lying around often made the travelers question why this was called the “pearl of cities” in the first place.

Istanbul seemed to save its worthy offerings for those who were patient enough to deserve them.

“A painted whore, the mask of deadly sin/Sweet and fair without, and stinking foul within,” wrote William Lithgow in his diary right after he entered his lodgings in Pera. And yet, just like the breathtaking scenery that welcomed them to the city, this foulness was also transient as Istanbul seemed to save its worthy offerings for those who were patient enough to deserve them. As our friend Lithgow later mused, “Notwithstanding all that, for its delicious wines, fruits, and delicacies, the temperate climate, the Bosporus, this may truly be called paradise on earth.”

An enviable idleness

“What a sad pity it is that we know nothing about making coffee in Europe.”

One of Istanbul’s pleasures that is ever present in every single travelogue is coffee. Always served black and steaming hot in tiny cups, Turkish coffee never fails to impress. Slowly cooked on a brazier, it elicits such an intense feeling of gratification that Julia Pardoe bemoans, “What a sad pity it is that we know nothing about making coffee in Europe.” With their coffee, travelers notice, Turks never fail to enjoy their pipes, so much so that the imagery of an Istanbulite sipping from a cup while puffing away at his pipe appears in almost every piece of travelogue from the 17th century onwards.

Henri Charles Antoine Baron - Un Turc fume couché (1844)

The image of the Turk enjoying his coffee and a pipe in a coffee house becomes so engraved in Western imagination that when Charles MacFarlane visits Istanbul in the mid-19th century, he is bemused by the shortage of coffee houses in the city. “Hundreds of barber shops and not a single coffee house,” he grumbles. His Greek guide laughs at the Englishman’s naivete, takes him to the closest barber shop, and once inside, pulls a curtain and opens the door behind. And, lo and behold, a handful of men, reclining on colorful sofas, are puffing away at their pipes with tiny cups in their hands. After explaining to the Englishman that Sultan Mahmud had ordered the suppression of coffee houses as they were only frequented by troublemakers, the guide adds: “But Turks, sir, well, they cannot live without their coffee houses.”

Charles Mac-Farlane, Constantinople et la Turquie, traduit de l’Anglaise par MM. Lettement, Paris, Moutardier, 1829

An image, however, is seldom merely an image and often reflects an underlying theme – in this case, idleness. And so tranquil is this idleness that it often stirs up a barely discernible wistfulness (or, perhaps even jealousy) from the authors. Discussing how Turks enjoy simple pleasures, Pardoe writes, “In terraced coffee houses that line up along the delicious nooks along the Bosporus, the Ottoman smokes his pipe, and inhales his tiny cup of mocha amid sights and sounds to which the world can probably produce no parallel.”

A city of pleasures, innocent and otherwise

Food is another source of immense pleasure for travelers visiting Istanbul. Those from London particularly draw attention to the abundance and variety of sweet fruits available (probably because of the lack of options in England at the time) and marvel at the fact that in Istanbul they are consumed at any and every hour of the day.

Pardoe, who, like her predecessor Montagu, enjoys visiting Turkish households, especially outside Pera, provides detailed lists of the many dishes her hosts offer. At a dinner she attends in the Turkish quarter of the city, where her host complains about not having enough time to prepare a “proper meal”, she counts 19 dishes on the table including anchovies, caviar, fish, poultry, meat, cold bread soup, rice, and of course, sweets. Her Greek hosts in Fener are at least as generous: homemade rose jam, pickled anchovies, dried sausages, tongue from Adrianople, fish, and shredded cheese.

Left: The City of the Sultan, and domestic manners of the Turks in 1836 Volume I. London: Henry Colburn, Publisher, Great Malborough Street. 1837.

Right: Portrait of Julia Pardoe, British poet, with her autograph at the bottom

Pardoe isn’t a picky eater but she most certainly has a favorite Istanbul dish: kaimak, clotted cream. She especially cannot forget the one she had while staying at Fener, which is no surprise, as unbeknownst to her, Istanbul’s most famous dairy farm was located merely a few kilometers away. The milk produced in the Eyüp dairy farm was so tasty (likely due to the quality of the pasture) that the district became famous for its kaimak. For more on Ottoman Istanbul’s dairy farms, see here.

However, if there was one traveler who truly enjoyed what Istanbul had to offer in terms of food and drinks, it was Albert Smith. From the outset of his memoirs/travelogue, it is apparent that

Smith is a man with plenty of joie de vivre; he doesn’t merely enjoy the pleasures that Istanbul has to offer but actively seeks them out. And that is why, the one month he spends in Istanbul in 1850 turns out to be an adventurous experience any traveler would have killed for.

One evening, with a few companions alongside him, Albert hires a caique and heads for Arnavutköy, a small village on the European shoreline of the Bosporus. There, they find a restaurant – nothing more than “a brazier sitting amidst a few low chairs” – and decide to taste the local flavors. “We had chopped mutton on skewers, cooked over fire, and served with pepper, salt, and finely chopped onions. There were no forks or knives but it was delicious… one of the finest meals I’ve ever had in my life.” On their way back, mesmerized by the beauty of Bosporus, Smith and his friends open a few bottles of beer they had brought along. Always the sharer, Smith offers a bottle to the caique owner who gladly accepts: “The gusto with which he drank the beer proved that the Moslem’s abhorrence of intoxicating drinks is not difficult to overcome.”

Albert Richard Smith in the 1850s

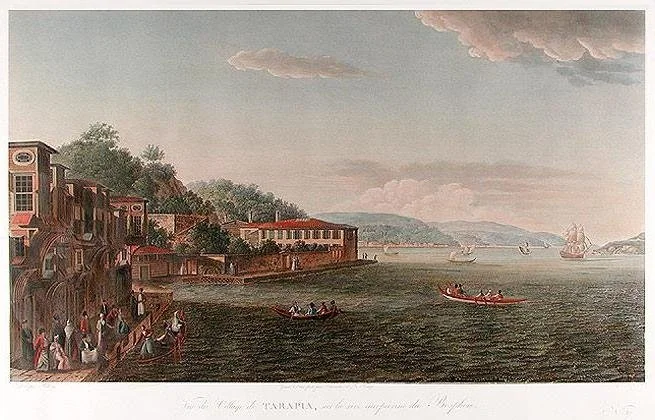

Realizing that there is much to enjoy outside Pera, Smith first visits Büyükdere (on the European shoreline of the Bosporus and a popular summer retreat for foreign diplomats in the 19th century) and spends the entire day in the gardens of Hotel de l'empire Ottoman watching the Bosporus and enjoying sausages, cheese, fruits, and delicious Greek wine. Then he spends a night in the neighboring Tarabya, “drinking copious amounts of pale ale I found in a shop nearby and eating swordfish.” Finally, he visits a monastery in Büyükada (the largest of the Princes’ Islands) and enjoys quite a few glasses of rakı brewed by the monks themselves. It is safe to say that indeed, no other traveler probably savored Istanbul like Smith did.

Ottoman villas at Tarabya, on the European shores of the Bosporus by Antoine Ignace Melling

The dogs of Istanbul and an unforgettable lesson

… “with the fragrant coffee steaming at my side and the soothing bubble of the narghiles sounding in every direction, I felt that single moment was worth all the torture and pain.”

Curiously enough, like with Lady Montagu, the city truly revealed itself to Smith during a visit to the bathhouse.

During one of the nights he spent in Pera, Smith is kept awake all night by the endless howling and yelping of Istanbul’s infamous street dogs. So, in the early hours of the morning, feeling exhausted and in need of refreshing, he visits one of the famous bathhouses in the city. After undressing and wrapping himself under the waist with a thin towel, “two savage, unearthly boys” seize him and force him onto the hot marble floor. They then commence “a dreadful series of tortures such as I had only read as pertaining to the Middle Ages.”

Photos Courtesy of Istanbul Research Institute

As the other customers start laughing at him, Smith finds himself contemplating the end of life and how cruel a game fate has played with him: “I felt sad that I’d meet my end in a foreign bath. And sadder that probably the dogs that kept me awake all night with their howling and yelping, the dogs that are the reason I am here, would be nibbling at my corpse in a few hours.” But then, all of a sudden, the boys wrap him in swathes of towel and let him be on his own. Lying on that marble, “with the fragrant coffee steaming at my side and the soothing bubble of the narghiles sounding in every direction, I felt that single moment was worth all the torture and pain.” Istanbul, in the blink of an eye, teaches Smith that it takes patience to truly savor what it has to offer. And he will not be the last person to realize how valuable that lesson is.

Further readings

Albert Smith. A Month at Constantinople. D. Bogue: London. 1850.

Elizabeth Craven. Journey through the Crimea to Constantinople. Gorgias Press: Piscataway, NJ. 2010

Julia Pardoe. The City of the Sultan and Domestic Manners of the Turks. Henry Colburn: London. 1836.

Sir Henry Blount. Voyage into the Levant. London. 1636.

William Lithgow. The Total Discourse of the Rare Adventures and Painful Peregrinations of Long Nineteen Years Travels from Scotland to the Most Famous Kingdoms in Europe, Asia, and Africa. James MacLehose and Sons: Glasgow. 1906.