Lady Mary Montagu and her Naked, Sapphic Istanbul

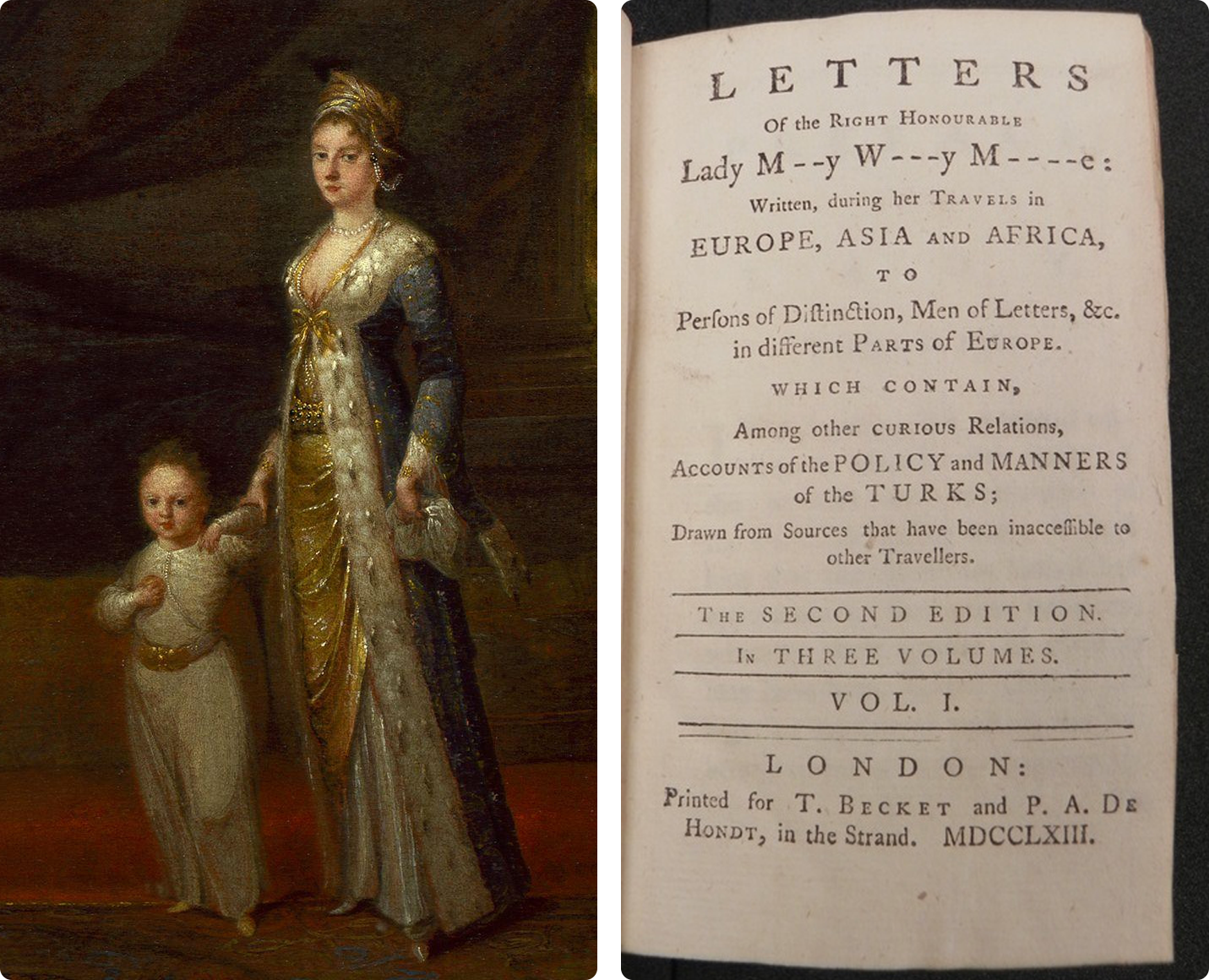

Lady Montagu in Turkish dress painting by Jean-Étienne Liotard

Born on 15 May 1689, Lady Mary was a bright, free-spirited child who spent her early youth teaching herself Latin, reading extensively, and writing poetry. By 1710, she had two suitors – Edward Wortley Montagu and Clotworthy Skeffington – and in 1712 she picked the former as her husband. Unbeknownst to her at the time, this decision would help her realize the childhood dream she had recorded in her diary at the age of eight: “I am going to write a history so uncommon!” Indeed, since its publication, her Embassy Letters has continued to be an inspiration to women travelers.

An Istanbul, no traveler had seen before…

Byzantium, Constantinople, or Istanbul – whichever of its nearly hundred names you call it by, this “queen of cities” has always been an object of attraction, if not desire, for the Western and predominantly European traveler. The likes of Gérard de Narval, Edmondo De Amicis, Alphonse de Lamartine, and François-René de Chateaubriand have been drawn to this “exotic” imperial capital like bees to honey. Frequently male and without exception white, these authors/travelers recorded, explained, judged, and very often built an intriguing love/hate relationship with Istanbul, whereby, while admiring its natural beauty, they abhorred its inhabitants and their ways of life. There were exceptions, however; exceptions such as Lady Mary Mortley Montagu.

In 1716, the first Hanoverian king of Great Britain, George I appointed Lady Mary’s husband Edward Wortley Montagu as Ambassador at Constantinople to negotiate an end to the Austro-Turkish War. The ambassadorship resulted in a total failure, but Lady Mary’s letters penned during her travels and time spent in Istanbul (until the summer of 1718) proved to be one of the best and most extraordinary examples of travelogue written hitherto.

Rgiht: Original Title Page to Montagu’s Turkish Embassy Letters (Credit: UBC Rare Books and Special Collections); Left: Painting of Montagu and her son Edward by Jean-Baptiste van Mour

English author Virginia Woolf and French Neoclassical painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres were particularly impressed by Lady Mary’s writings. Woolf is said to have based her depictions of Istanbul in Orlando on Montagu’s letters, while Ingres’s The Turkish Bath was inspired by her descriptions of Turkish bathhouses, or bagnios.

“I live in a place that represents the Tower of Babel… Even in my own household, there are ten different languages spoken!”

The letters she wrote during her first six months in the capital include everything you’d expect to see in an 18th-century travelogue. She expresses joy in being able to sit in her chambers with windows open in winter months, surrounded by fresh carnations, roses, and jonquils from her garden. She admires the Grand Bazaar as the most “opulent international Emporium” she has ever set eyes on. She is left speechless by the beauty of the Bosporus and baffled by the number of languages spoken in Pera, where most of the foreigners living in the capital resided: “I live in a place that represents the Tower of Babel… Even in my own household, there are ten different languages spoken!” But then something changes. And, as she learns Ottoman (enough to express herself and understand others) and gets to know the city better, a different, more enticing, more titillating Istanbul is laid bare before our eyes – literally and figuratively.

Lady Montagu’s Istanbul is charged with homoerotic desire and is unambiguously sapphic in nature.

This naked Istanbul of whose truth she wants to write on so “others can avoid being misled by the writings of travelers, many of whom pass years here without seeing it” reveals itself to her primarily because she is a woman. She has access to that single space no man can even dream of entering: the world of Ottoman women. And as she becomes more acquainted with these women, she “cannot forbear admiring the extreme stupidity of all writers that have given accounts of them.” This is an unequivocal declaration of war on the male-dominated world of travelogues and Lady Mary does not shy away from admitting so:

“I am malicious enough to desire that the world should see how much better purpose the ladies travel than their lords…Ladies can embellish a worn-out subject with a variety of fresh entertainment.”

Panorama of Istanbul by Antoine de Favray (1773)

So, what does Lady Montagu’s Istanbul, the truer Istanbul, look like? Well, it is charged with homoerotic desire and is unambiguously sapphic in nature.

Take her encounters with Fatima, a Turkish woman of good standing, whose “beauty effaced everything around her.” Her radiance is so overwhelming that when Lady Mary first sets eyes on her, she cannot for some time utter a single word: “That harmony of features! That exact proportion of the body! That lovely bloom of complexion! The unutterable enchantment of her smile! I am not ashamed to own, I took more pleasure in looking on the beauteous Fatima than the finest piece of sculpture could have given me.” And her admiration is not unrequited.

When the two women meet for the second time, in Fatima’s private chambers, they shower each other with compliments befitting a Charlotte Brontë novel. Lady Mary tells Fatima if all Turkish women are as beautiful as her, “it is absolutely necessary to confine them from public view for the repose of mankind” and then adds: “What noise a face as yours would make in London!” Fatima is swift and at least as witty with her reply: “I don’t believe you. If beauty was so much valued in your country as you say, they’d never have suffered you to leave it.”

As Lady Mary gets to know the city better, a different, more enticing, more titillating Istanbul is laid bare before our eyes – literally and figuratively.

Lady Mary’s relationship with Fatima remains confined to exchanging words of affection and adoration, but she never ceases to identify her beauty with that of Istanbul. So much so that the two become interchangeable; both Istanbul and Fatima are forbidden to men and reveal their true nature and beauty only to Lady Mary (and, perhaps, to other women). Her conviction that only women can set foot in this “true Istanbul” is further reinforced following a visit to a local bagnio, where she experiences an indelible carnal spectacle.

Le Bain Turc by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

After she enters the bagnio, Lady Mary realizes a bridal ceremony is about to take place and decides to observe what “a man would not even be allowed a peek into.” The bride’s married friends place themselves around the room on marble sofas, but the “virgins hastily throw off their clothes and appear without other ornament or covering than their own hair.” Two of them meet the 17-year-old, richly dressed bride at the door and presently “reduce her to the state of nature”. Then, thirty more virgins surround and bathe her in sweet perfume: “It is not easy to represent to you the beauty of this sight, most of them being well-proportioned and white-skinned, all of them perfectly smooth and polished by frequent use of bathing.” The climax of the scene occurs when the young women approach Lady Mary and ask her to undress. Although she refuses at first, they manage to persuade her to “open my shirt and show them my stays, which satisfied them very well.” Undoubtedly, their satisfaction pleases Lady Mary.

So, Lady Mary wages a battle against men to prove that she and other women can be better travelers and that they can have access to realms men dare not even dream of glancing at. She wages that battle through Istanbul and the city becomes her ally, proving that she indeed is the better traveler as she was allowed to look into the heart of the queen of cities. Her gaze is not that of an objectifying, reifying man but that of an affectionate and desirous companion. And so it is that Lady Mary converses with Istanbul, interacts with it, and understands it like none of her predecessors could.

Further readings

Letters of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. London: Thomas Martin.

Mary Mortley Montagu. Life on the Golden Horn. Penguin: London. 2007